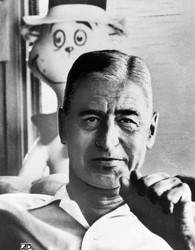

Theodor Geisel, more popularly known as Dr. Seuss, created quirky characters, lively rhymes and idiosyncratic illustrations. These qualities have ensured that his children’s books have remained enduringly beloved while they promote strong moral values. Seuss’ 44 books have been translated into more than 20 languages.

Theodor Geisel’s Early Days

Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on March 2, 1904, in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father was a brewmaster and his mother the daughter of a baker.

As a young woman, his mother worked in her father’s shop, where she memorized the names of each pastry to recite to her customers. When Geisel was a young boy, she often recited her “pie-selling chants” to lull him to sleep, recount Judith and Neil Morgan in the biography “Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel.” Later in life, Geisel would attribute his poetic impulses to his mother’s rhyming.

As a young man, Geisel attended Dartmouth College, where he worked on the Jack-O-Lantern, the college’s humor magazine. Geisel’s role at the paper was threatened when he and his fraternity brothers were caught throwing a party in violation of school rules. In order to continue contributing to the publication, Geisel adopted the pseudonym “Seuss,” which was easily identified by his classmates, but unrecognizable to school officials.

Geisel was not a great student. Nevertheless, he ended up at Oxford, where the drawings he made during class caught the attention of a fellow American student, Helen Palmer, who suggested Seuss become an artist instead of a professor. Geisel took her advice, and married her as well.

Sources in this Story

- Random House: Seussville: Dr. Seuss

- UC San Diego Libraries: The Advertising Art of Dr. Seuss

- PBS: Independent Lens: The Political Dr. Seuss

- The New York Times: Laughter’s Perennial at the Doctor’s Seussentennial

- The History News Network: The Messages You May Have Missed Reading Dr. Seuss

Dr. Seuss’ Books and Other Works

Geisel began his artistic career as a cartoonist in New York City. He submitted an illustration to The Saturday Evening Post, which was accepted and published. The cartoon got the attention of the editor of Judge, a New York weekly, who put Geisel on staff.

Standard Oil also offered him a job in their advertising department. The artist spent nearly 15 years in advertising, primarily working for Standard, but also contributing drawings to magazines and publications like Judge, Life and Vanity Fair.

In addition, Geisel illustrated more than 400 political cartoons in the progressive New York publication PM and served in Frank Capra’s Signal Corps, making animated training films for the U.S. Army. He also contributed to two Oscar-winning films, “Your Job in Germany” and “Your Job in Japan.”

Geisel published his first children’s book, “And to Think That I Saw it on Mulberry Street,” in 1937. The book was rejected 27 times by 27 different publishers until finally being accepted by the Vanguard Press, thanks to a fellow Dartmouth alumnus who was employed there.

Next, Geisel was commissioned to write a reading primer. “The Cat in the Hat” revolutionized the way young children learn to read because it made the process fun. After that, he had no trouble publishing his work, and dedicated himself full-time to children’s book writing.

Geisel wrote more than 40 books, including “How the Grinch Stole Christmas,” “Oh, the Places You’ll Go,” “Green Eggs and Ham,” “The Butter Battle Book,” and “The Lorax.” Several of his works were adapted into animated films that are now considered classics. During his career, he picked up two Emmy awards, a Peabody award and the Pulitzer Prize.

The Man and His Work

- “Six by Seuss: A Treasury of Dr. Seuss Classics”

- “The Cat in the Hat”

- “Green Eggs and Ham”

- “The Sneetches and Other Stories”

- “Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel” edited by Richard H. Minear

The Rest of the Story

Theodor Seuss Geisel died in 1991 at the age of 87 in La Jolla, California. His books have been translated into 21 languages, including Braille, and have sold more than 500 million copies.

Geisel’s legacy lives on his books, his films and in several locations that honor his work. The Geisel Library in La Jolla holds more than 8,000 archived items, including the original sketches of “The Cat in the Hat.” There is also a sculpture garden dedicated to Dr. Seuss’ most famous characters in his hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts.

Despite the cheerful tone of his books, Geisel was deeply preoccupied with social and moral values. Although he claimed not to have purposefully written moralizing books, his children’s fiction promotes social, environmental and political messages.

According to Messiah College history professor John Fea, “Geisel struggled to balance a common-sense faith in personal rights with a commitment to the public good. He seemed to realize that individualism, while essential to any democratic society, was often not sufficient to sustain the kind of community needed for a republic to survive.”

This article was originally written by Isabel Cowles; it was updated January 12, 2017.