At the end of his life, D.H. Lawrence wrote, “For man, as for flower and beast and bird, the supreme triumph is to be most vividly, most perfectly alive.” His work always strove to reconcile the needs of the body with an intellectual existence; however, in his life, his sickly body often held back the progress of his gifted mind.

D.H. Lawrence’s Early Days

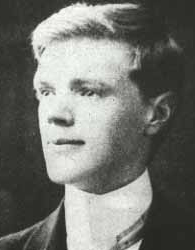

David Herbert Richards Lawrence was born on September 11, 1885, in Eastwood, England. He had a deeply troubled family life that played a part in the angst-ridden personality he became. Not only was Lawrence isolated at school, but his unhappy and possessive mother did her best to turn her children against their drunken and temperamental father, although she also tried to ensure that her children would grow up to have a better life.

To that end, “Bert,” as he was then known, ultimately became a teacher and went to college to get a certificate. Although he was not enthusiastic about college, he was enthusiastic about the challenges of being a teacher. He pursued that career until the weak lungs that had plagued him since birth made him too ill to work.

Meanwhile, his writing career had been burgeoning and helped him make a life-changing move to London. Although he eventually moved home and married a professor’s daughter, Frieda Weekley, his literary life had already taken root.

Sources in this Story

- University of Nottingham: Extended Biography of D.H. Lawrence

- Academy of American Poets: D.H. Lawrence

- Celestial Timepiece: Joyce Carol Oates on D.H. Lawrence

- Encyclopedia Britannica: D.H. Lawrence

- The New Yorker: The Lady at the Old Bailey

- The New Yorker: The Deep End

- The Guardian: DH Lawrence

Lawrence’s Literary Work

Lawrence is better known as novelist than as a poet, but the Academy of American Poets notes that his poetry was published before his novels or stories. He was extremely devoted to poetry, and was fond of writing about animals.

“Lawrence’s poems are blunt, exasperating, imposing upon us his strangely hectic, strangely delicate music, in fragments, in tantalizing broken-off parts of a whole too vast to be envisioned—and then withdrawing again,” wrote author Joyce Carol Oates in the American Poetry Review. “They are meant to be spontaneous works, spontaneously experienced; they are not meant to give us the sense of grandeur or permanence that other poems attempt, the fallacious sense of immortality that is an extension of the poet’s ego.”

His novels, often scathingly autobiographical, have carved a significant space for themselves in the literary canon. For example, “Sons and Lovers” is believed to be based on his childhood experiences and his relationship with his mother.

Lawrence’s last novel was perhaps his most famous (or infamous) book, the sexually explicit “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” which concerns the characters’ attempts to balance intellectual and physical pleasures in life, a theme that also appears in his novels “The Lost Girl” and “Sons and Lovers.”

“Lady Chatterley’s Lover” was published in 1928, but was not widely available until after an obscenity trial in England and another in New York.

The Man and his Work

- “Lady Chatterley’s Lover”

- “Sons and Lovers”

- “The Lost Girl”

- “The Rainbow”

- “D.H. Lawrence: Complete Poems”

The Rest of The Story

Lawrence’s health particularly suffered during the First World War; he and his wife were also suspected of being German sympathizers. As soon as the war ended, they left England, never to return.

His later writing focused on the physicality of human and animal life: “By the nineteen-twenties, Lawrence wants his writing to indicate, and his readers to embrace, the animal aloneness that human language only seems to overcome; bodies may come into contact, but not soul,” writes Benjamin Kunkel in The New Yorker.

He continued to write until his death on March 2, 1930, from tuberculosis, which had rendered his body useless and deteriorated. Always prone to writing in the voice of animals, he weighed 85 pounds when he died and his wife said that he was buried “simply, like a bird.”

Lawrence had a complicated, multifaceted personality, often presenting himself differently to different people. “Oppositions were … both natural to him, and a conscious choice,” writes John Worthen, director of the D.H. Lawrence Centre at the University of Nottingham.

His work is similarly seen in differing and conflicting lights. “Lawrence has always provoked strong reactions in his readers: shock from his censors during his lifetime; engrossment from adolescents who encounter his work at school; ridicule from critics who parody his overblown prose and fondness for lubricious episodes,” writes The Guardian.

His blunt depictions of sexuality have caused controversy, earning him both condemnation and praise “as a pioneer of a ‘liberation’ he would not himself have approved,” writes Lawrence scholar Michael H. Black. Since the 1960s, his work has often been deemed misogynistic.

“Cultural mores aside, however, DH Lawrence at his best is spellbinding,” says The Guardian. “Boldly experimental and deeply sensual, he is a working class hero who heralded the modern age through both his radical style and his unabashed celebration of sexual relationships.”

This article was originally written by Rachel Balik; it was updated September 3, 2017.