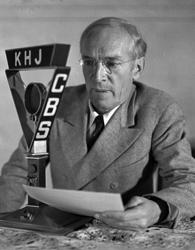

Best known for exposing horrific practices in the meatpacking industry with his novel, “The Jungle,” Upton Sinclair was more than just a muckraker. From organizing a utopian commune to running for office, the sworn socialist was relentless in his quest for reform.

Upton Sinclair’s Early Days

Born on September 20, 1878, Upton Sinclair was the only child of an alcoholic, Upton Beall Sinclair, and a society dame, Priscilla Harden Sinclair. With a mother who came from a wealthy Baltimore family and a father who drifted in and out of destitution, Sinclair had an early lesson in class struggle.

“… [A]s far back as I can remember my life was a series of Cinderella transformations; one night I would be sleeping on a vermin-ridden sofa in a lodging house, and the next night under silken coverlets in a fashionable home. It all depended on whether my father had the money for that week’s board,” Sinclair once said, describing his childhood.

As soon as he was able, Sinclair began to earn his own keep. In high school, he published his first story in Argosy magazine and then moved on to selling jokes and stories to Life, Judge and Puck magazines.

Sinclair graduated from City College in New York and then attended lectures at Columbia University. Meanwhile, he maintained a career as a writer, producing up to 8,000 words a day.

Sources in this Story

- The Baltimore Literary Heritage Project: Upton Sinclair

- The New York Times: Upton Sinclair, Author, Dead

- Slate magazine: Welcome to The Jungle

- The New York Times: Blood and ‘Oil!’

- Oxford University Press blog (The American National Biography): Happy Birthday Upton Sinclair

- Time: California Climax

- Social Security Online History Pages: Upton Sinclair

Sinclair’s Notable Accomplishments

Despite earning a Pulitzer for a later work, nothing Sinclair wrote ever eclipsed the fame of his exposé, “The Jungle.” The 1906 novel was intended to spotlight dangerous and unfair working conditions in turn-of-the-century meat factories. Instead, it inspired a generation of vegetarians and a host of new food safety regulations, including one that ultimately led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

“I aimed at the public’s heart,” Sinclair notoriously lamented, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

Other muckraking books followed. In 1917, “King Coal” explored tragedies that befell workmen on strike at the Colorado Coal and Iron Company. “The Profits of Religion” cast a suspicious glance on money-hungry clergy, and “Oil!” explored abuses in California’s oil industry. (The 2007 blockbuster film, “There Will Be Blood,” was based on “Oil!” and won many awards, including two Oscars.)

It seemed no group was spared Sinclair’s critical pen: he dissected the subsidized press, educational system, the Ford Motor Company and the 1920s Sacco-Vanzetti case, which challenged people’s ideas about civil liberties.

Later in his career Sinclair turned to historical novels. He wrote a series of 11 books featuring a journalist protagonist, Lanny Budd, who narrated historical events from 1913 through 1939.

It was for the third book in this series, “Dragon’s Teeth” that Sinclair won the Pulitzer Prize in 1943. Despite the fact he wrote more than 100 books, this Pulitzer was the only major literary award ever won by the prolific writer.

Upton Sinclair and his Work

The Rest of the Story

Upton Sinclair was not content to simply write books about change; he wanted to effect that change himself. He was extremely active within the Socialist Party and used his profits from “The Jungle” to build a commune to further his socialist ideals. Helicon Hall, located in Englewood, New Jersey, only lasted a year before burning down, but attracted hundreds of Sinclair’s colleagues, including Sinclair Lewis, who served as the commune’s janitor.

Sinclair also made several bids for political office, running for the House of Representatives in 1906 and 1920 and for the Senate in 1922. He also ran for governor of California in 1926, 1930 and 1934. His first few races were on the Socialist ticket, but by 1934, he campaigned as a Democrat who promoted socialist ideals and very nearly won the seat.

In addition to politics and scandals, Sinclair was also keenly interested in psychic phenomena. He published a book about telepathy and his second wife, Mary Craig Sinclair, was at one time tested for psychic abilities.

Sinclair died in his sleep in a nursing home on November 25, 1968, at the age of 90.

This article was originally written by Jennifer Ferris; it was updated September 12, 2017.