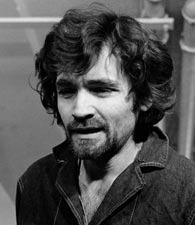

On March 29, 1971, a jury sentenced Charles Manson and three members of his “Family” to death for murdering actress Sharon Tate and seven others.

Manson Family Convicted of Tate-LaBianca Murders

Charles Manson was the leader of “the Family,” a cult-like group of mostly young women recruited from the streets of San Francisco. Claiming to be Jesus Christ, Manson told his recruits that they needed to carry out a violent racial war as part of a prophecy he referred to as “Helter Skelter.”

On August 9, 1969, he ordered followers Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, Linda Kasabian and Charles “Tex” Watson to attack the home of director Roman Polanski. They first killed a teenager, Steven Parent, in the driveway and then broke into the home, where they brutally murdered Polanksi’s pregnant wife Sharon Tate and three of her guests: Voytek Frykowski, Abigail Folger and Jay Sebring.

The following night, Manson led the same four plus two other followers, Leslie Van Houten and Steve Grogan, a.k.a. Clem Tufts, in the murder of couple Leno and Rosemary LaBianca.

The Family initially avoided suspicion for their crimes, but in October Manson and 23 others were arrested on unrelated charges of arson and grand theft. In November, Atkins told a fellow inmate that she has participated in the Tate and LaBianca murders. She later described the murders to a grand jury, which returned indictments against Manson, Krenwinkel, Atkins, Kasabian, Van Houten and Watson (who would be tried separately because he needed to be extradited from Texas).

Atkins would decline an opportunity to testify at trial to avoid the death penalty. The prosecution then turned to Kasabian, who had not taken active part in the murders and who had showed remorse, to be its primary witness in exchange for immunity from prosecution. Kasabian’s testimony, which was corroborated by many other witnesses, would form the core of the prosecution’s case.

Manson arrived in court for the first day of testimony with an “X” carved in his forehead; the X was transformed into a swastika as the trial progressed.

The girls copied Manson’s X and behaved erratically in court, frequently giggling and sometimes chanting in Latin. Judge Charles Older ejected the defendants from the courtroom on several occasions.

On October 5, Manson grabbed a pencil and jumped over the defense table toward Older, exclaiming, “In the name of Christian justice, someone should cut your head off.”

The prosecution rested its case on November 16. When asked to present the defense’s case, the attorneys for the three girls said they would not call any witnesses, causing their clients to vocally object in court. The attorneys argued that the girls were still under the influence of Manson and that they would incriminate themselves to save Manson.

Manson volunteered to take the stand so the girls would not have to. During his testimony, which took place on November 20 without the jury present, Manson declared, “I can’t dislike you, but I will say this to you: you haven’t got long before you are all going to kill yourselves, because you are all crazy. And you can project it back at me…but I am only what lives inside each and every one of you.”

The case was delayed for a month after Ronald Hughes, the attorney for Van Houten, disappeared during a camping trip on November 30. He was later found dead in the woods; there is speculation that he was murdered by Manson followers.

On January 25, 1971, Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten were convicted of first-degree murder. Two months later, on March 29, they were sentenced to death by gas chamber.

University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law provides excerpts from the trial transcript, a timeline of events, biographies of the defendants and other trial figures, and a look at Manson’s beliefs and influences.

Sources in this Story

- University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law: The Manson Trial

- The New York Times: Charles H. Older

- CNN: Aging Manson ‘Family’ members long for freedom

- Los Angeles Times: Gov. Jerry Brown denies parole for former Manson Family member

- Los Angeles Times: Charles Manson follower Susan Atkins dies at 61

- Rolling Stone: Manson Family: Where Are They Now?

- CNN: At 75, Charles Manson still has power to influence others

- Time: The Girl Who Almost Killed Ford

The Manson Family in Prison

All four defendants—along with Watson, who was sentenced to death in a separate trial—would have their sentences commuted to life in prison after California abolished the death penalty in 1972.

Van Houten’s conviction was overturned in 1976 after a court ruled that there should have been a mistrial after her attorney went missing. She was tried again twice and convicted of murder in 1978. The Parole Board recommended she receive parole in 2016, which led to a backlash from the public, including Tate’s sister. Governor Jerry Brown denied her parole in July 2016.

Van Houten and Krenwinkel were described as “model prisoners,” according to CNN, but their appeals for parole have been consistently denied. Watson, who has become a minister, also remains in prison.

Atkins, who had also been a well-behaved inmate, died on September 24, 2009, of brain cancer, just three weeks after she was denied parole for the 18th and final time.

Manson, now 82, was last denied parole in 2012. He remains in Corcoran State Prison, where he still receives visitors from people interested in his beliefs.

“There’s a certain mystique that has developed around Manson,” said Vincent Bugliosi, who prosecuted Manson, to CNN. “And one reason is that the very name Manson has come to be a metaphor for evil. He’s come to represent the dark and malignant side of humanity, for whatever reason, people are fascinated by pure, unalloyed evil.”

Manson had a health scare in early 2017 and spent time in a hospital before being returned to prison.

Related Topic: “Squeaky” Fromme

Some of Manson’s followers continued their devotion even after he was put away. Perhaps the most notable is Lynette Alice Fromme, known as “Squeaky” for her high-pitched voice, who became the first woman ever to attempt to kill a president of the United States.

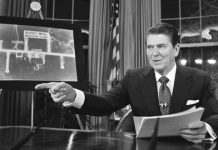

The 27-year-old woman attempted to shoot President Gerald Ford while he made his way through admirers in a Sacramento park during the 1976 presidential election campaign, but was apprehended by Secret Service just in time.

Dulcinea Media Store

Vincent Bugliosi describes the events that surrounded the murders in “Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders.”

The 1989 documentary “Charles Manson Superstar,” written and directed by Nikolas Schreck, includes an interview with the killer himself.