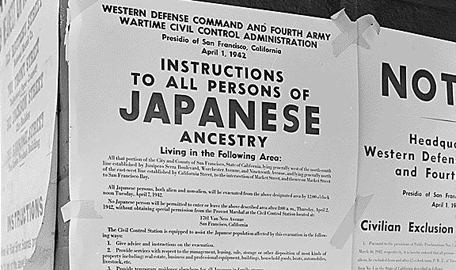

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the military to relocate Japanese-Americans from their homes to internment centers.

Executive Order 9066 Authorizes Japanese Internment

Japan launched a surprise attack on a U.S. Naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, prompting President Roosevelt to declare war on Japan the next day. The attack fueled anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States, and many in the government and public suspected that Japanese-Americans had collaborated in the attack.

The FBI immediately arrested hundreds of Japanese and German aliens it suspected of disloyalty. However, with West Coast residents living in fear of another attack, many politicians and military men asked the federal government to detain all Japanese immigrants and natural-born citizens of Japanese descent.

The Roosevelt administration debated how it could legally carry out a mass detainment. “Department of Justice representatives raised constitutional and ethical objections to the proposal, so the U.S. Army carried out the task instead,” according to the National Archives’ Our Documents.

One adviser to Roosevelt sent him a memo saying that he must take action to “preserve national safety, not for the purpose of punishing those whose liberty may be temporarily affected by such action, but for the purpose of protecting the freedom of the nation, which may be long impaired, if not permanently lost, by nonaction.”

On February 19, 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, allowing the military to create military areas and exclude any persons from those areas at its discretion. These excluded people would be given accommodations provided by the military. The measures were justified, according to the order, because “successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage.”

On March 2, the military designated the western halves of California, Oregon, and Washington, and the southern part of Arizona as military zones. Japanese-Americans were ordered to leave these areas, and Roosevelt soon signed an act allowing the military to forcibly remove those who refused to leave.

Sources in this Story

- U.S. Army Center of Military History: Command Decisions: The Decision To Evacuate the Japanese From the Pacific Coast

- Our Documents: Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese (1942)

- Harry S. Truman Library and Museum: The War Relocation Authority & the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during WWII

- PBS: Children of the Camps: Internment History

- George Mason University: History Matters: Executive Order 9066: The President Authorizes Japanese Relocation

The Internment of Japanese-Americans

The federal government created the War Relocation Authority, which oversaw the removal of 120,000 Japanese-Americans from military areas over the next 18 months. The Japanese were forced from their homes and taken to 10 internment camps in remote areas in eastern California, northern Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas.

“The government made no charges against them, nor could they appeal their incarceration,” according to Our Documents. “All lost personal liberties; most lost homes and property as well.”

Conditions in these camps were poor and Roosevelt himself called them “concentration camps.” PBS cites the book “Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians,” which provides a description of the camps: “In the detention centers, families lived in substandard housing, had inadequate nutrition and health care, and had their livelihoods destroyed: many continued to suffer psychologically long after their release.”

The constitutionality of exclusion was challenged in three Supreme Court cases. In the last two, both decided on December 18, 1944, the court ruled that exclusion itself was constitutional, but exclusion of loyal citizens was not. The War Relocation Authority had just prior to the decisions decided to begin closing camps, a process that lasted until 1946, after World War II had ended.

Resources for Learning About Japanese-Internment

The National Archives features official documents relating to the relocation and internment program, including detention and internment files, public hearings and testimonies, and an index of compensation and reparation case files. It also provides a teacher’s guide.

The Smithsonian Institution’s “A More Perfect Union” gives an overview of internment, provides a collection of more than 800 artifacts, and includes a teacher’s guide. The Smithsonian also examines internment through four letters written by internees to a San Diego teacher.

The Manzanar (Calif.) National Historic Site, the site of a war relocation center, describes life in the camp, features oral history interview with former internees, and provides lesson plans for elementary and high school teachers.

The Library of Congress has a large collection of internment camp photos taken by famed photographer Ansel Adams.

George Takei, an actor perhaps best known for playing Hikaru Sulu on the television series Star Trek, was a child when his family was moved to an internment camp in Arkansas. He produced and starred in Allegiance, a musical partly based on his experience that debuted on Broadway in 2015.

Background: Pearl Harbor

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched an aerial attack on a U.S. Naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Two waves of Japanese planes dropped bombs, torpedoes and other incendiary devices, killing 2,400 Americans, sinking or damaging 21 vessels of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and destroying 188 aircraft within two hours.

The next day, in a speech to Congress, President Roosevelt called December 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy.” After the speech, Congress passed a declaration of war against Japan.

Related Topic: Internment of Germans and Italians

Executive Order 9066 was signed specifically to intern Japanese-Americans, but it was also used to intern American residents of German and Italian descent. According to George Mason University’s History Matters, 3,200 Italians and 11,000 Germans were arrested, while more than 300 Italians and 5,000 Germans were interned.