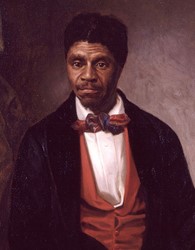

On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court ruled against Dred Scott, a slave who sued for freedom after spending time in free territory. The decision, which declared that slaves were not citizens and that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, outraged Northerners and contributed to the start of the Civil War.

Court Issues Ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford

Dred Scott was a black slave who was taken from St. Louis, Missouri, where slavery was legal, to the state of Illinois and to Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was prohibited, by his master Dr. John Emerson in the 1830s.

Scott spent roughly a decade in the free areas, which “gave him the legal standing to make a claim for freedom,” explains PBS, but he “never made the claim while living in the free lands—perhaps because he was unaware of his rights at the time, or perhaps because he was content with his master.”

Scott, along with his wife Harriet, had returned to St. Louis by 1843, when Emerson died and left control of the Scotts to his widow, Irene Sanford Emerson. Three years later, after unsuccessfully trying to buy his freedom, Scott sued for his freedom in St. Louis Circuit Court.

After 11 years of cases in the circuit court and Missouri Supreme Court, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1855. The case, Dred Scott v. Sandford (the court misspelled the name of John Sanford, Mrs. Emerson’s brother, who had assumed control of the case) was argued in 1855 and again in December 1856.

Six of the nine justices opposed Scott’s bid for freedom, and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, a defender of slavery, was selected to write the majority opinion. Newly elected President James Buchanan wrote to Justice Robert C. Grier of Pennsylvania, asking him to join the majority so that the case wouldn’t be settled along sectional lines. Grier agreed, and on March 6 Taney announced to a packed courtroom that the court had decided 7-2 against Dred Scott.

The court ruled that blacks had no rights of American citizens. “They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and, so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” wrote Taney.

Because Scott had no rights, he had no right to sue in federal court, and thus his case was rejected. Taney, however, was not content just to decide the fate of Dred Scott; he also hoped to decide the issue of slavery in America.

He declared the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which banned slavery north of 36 degrees 30 minutes north latitude, unconstitutional. He argued that Congress did not have the right to establish laws that infringed on a citizen’s right to own property—in this case, the right to own slaves.

Washington University of St. Louis’ Dred Scott Case Collection features the court papers from Scott’s 11-year legal battle, including the full Supreme Court decision.

Related Events

Analysis: The Effect on Slavery and the United States

The Dred Scott decision came at a divisive time in American history. The issue of slavery was threatening to tear apart the country, as pro-slavery and anti-slavery pioneers engaged in bloody conflicts in Kansas Territory, and abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner was nearly beaten to death by a Southern senator on the Senate floor.

Legislative attempts to address the slavery issue, such as the Compromise of 1850, had only delayed the need for a solution on slavery. Thus, when the Supreme Court heard the Scott case, it was addressing not just one man’s freedom, but the institution of slavery.

The case sparked outrage in the North. The Evening Journal, a Republican newspaper in Albany, New York, wrote of the decision: “Unworthy of the Bench from which it was delivered, unworthy even of the previous reputation of the jurist who delivered it, unworthy of the American people, and of the nineteenth century, it will be a blot upon our National character abroad, and a long-remembered shame at home…It falsifies the most reliable history, abrogates the most solemn Law, belies the dead and stultifies the living,—in order to make what has heretofore been a local evil, hereafter a National institution!”

The decision further divided the country and contributed to the start of the Civil War four years later. “The country was a tinderbox, and now the Supreme Court had lit a match…For the first time, Northern anger was not directed only at the expansion of slavery but at the South,” writes Gregory J. Wallance in Civil War Times.

The controversy strengthened the anti-slavery movement and the Republican Party—which rallied around Abraham Lincoln, who helped build his career denouncing the decision in an June 1857 speech, his June 1858 “House Divided” speech and his second debate with Senator Stephen Douglas—and weakened the Democratic Party, which splintered over the issue of a national slave code.

“Had it not been for such division, Lincoln’s election might have been doubtful…It may fairly be said that Chief Justice Taney elected Abraham Lincoln to the Presidency,” wrote Charles Warren in “The Supreme Court in United States history.”

Lincoln, running against three Democratic candidates, won the 1860 presidential election with less than 40% of the popular vote. Fearing that the election threatened the future of slavery, seven Southern states seceded before Lincoln’s inauguration, leading to the Civil War.

Contemporary Newspaper and Journal Articles

Furman University provides a collection of editorials about the case from March and April 1857.

The Library of Congress’ Slaves and the Court collection includes several legal reviews of the case.

Sources in this Story

- PBS: Dred Scott’s fight for freedom

- HistoryNet (Civil War Times): Dred Scott Decision: The Lawsuit That Started The Civil War

- University of Virginia: Scartoons: Racial Satire and the Civil War: The Road to 1860

- Missouri State Archives: Missouri’s Dred Scott Case, 1846-1857

Biography: Dred Scott

Dred Scott was born into slavery around 1800 in Virginia. In 1830, he was taken to Missouri, which 10 years earlier had been admitted into the union as a slave state under the Missouri Compromise. Soon after, Scott was sold to Dr. John Emerson, a military surgeon.

Emerson’s military career took him to posts in Illinois, a free state, and the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was prohibited under the Missouri Compromise. During this time, Scott married Harriet Robinson, with whom he would later have two children.

In 1837, Emerson traveled to St. Louis and later Louisiana, leaving behind Dred and Harriet Scott, who were hired out. The following year, Emerson sent for the Scotts to come to Louisiana. They traveled unaccompanied down the Mississippi River, choosing not to escape.

After Dr. Emerson’s death, Scott tried to buy his family’s freedom for $300 but Mrs. Emerson refused, compelling him to sue for his freedom. Though he eventually lost his court case, Scott gained his freedom just months later. Mrs. Emerson had married a prominent abolitionist, who was outraged to learn that his wife owned slaves and ordered her to release them.

Dred Scott and his family were freed on May 26, 1857. Scott worked at a St. Louis hotel, where he was treated as a celebrity until his death on September 17, 1858, of tuberculosis.

Historical Context: Slavery and the Civil War

The findingDulcinea Web Guide to Slavery in America and Web Guide to the Civil War links to the best primary and secondary sources for learning about the topics.

This article was originally written by Denis Cummings; it was updated January 15, 2017.