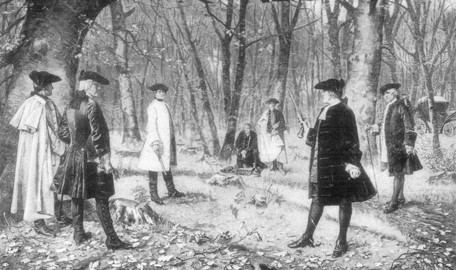

On February 20, 1839, Congress passed legislation barring the practice of dueling in the District of Columbia.

Fatal Duel Between Congressmen Prompts Ban

The passage of the law was inspired by a 1838 duel in which Kentucky Representative William Graves killed Maine Representative Jonathan Cilley at the infamous Bladensburg Dueling Grounds near the District of Columbia-Maryland border. The House, choosing not to censure Graves or the two other congressman present at the duel, instead presented a bill to “prohibit the giving or accepting within the District of Columbia, of a challenge to fight a duel, and for the punishment thereof.”

The law did little to deter dueling, according to Jennie C. Meade of George Washington University. “Although this measure assuaged public demand for a ban on dueling, like most dueling laws it proved ineffective, and duelists continued to meet at Bladensburg, mostly in the darkness.”

Sources in this Story

- Office of the Clerk: A fatal duel between Members in 1838

- George Washington University: The Duel

- PBS: The Duel

- Smithsonian Magazine: Duel!

- The New York Times: Killed in a Duel, Then Lost in the Earth

- HistoryNet (Civil War Times): Abraham Lincoln Prepares to Fight a Saber Duel

The History of Dueling

Dueling is an ancient practice that was originally a legal means to settle disputes in barbarian Germanic tribes, writes Meade. The use of “judicial duels” spread through Europe and remained in use as late as the early 19th century, though by this time the most common form of duels were “duels of honor,” which emerged after the medieval period.

Duels of honor, fought primarily between noblemen, were an extralegal means to defend one’s honor against personal insults. These duels were governed by codes, the most famous of which is the Code Duello, a list of 26 rules drafted in 1777 by Irish duelers. An American version of the code was drafted in 1838 by South Carolina Gov. John Lyde Wilson.

Under the code, a duel was negotiated through companions of the two duelers, known as “seconds.” The offended party would issue a challenge; the challenger could either apologize or accept a duel using the weapon of his choice (usually pistols, but swords were also allowed).

In America, duels were most prevalent in the South, particularly among upper-class gentlemen. Men who were challenged to a duel were expected to accept; those who refused faced public embarrassment. One South Carolina general, recalling a duel in his youth, remarked, “Well I never did clearly understand what it was about, but you know it was a time when all gentlemen fought.”

Even those who opposed dueling, such as Sam Houston, Henry Clay and Alexander Hamiliton, participated in duels due in large part to the social pressure. “For a man who wanted a political future, walking away from a challenge may not have seemed a plausible option,” writes Ross Drake in Smithsonian Magazine.

Though some states had laws against dueling, they were rarely enforced by the law enforcement or the courts. PBS explains that a shift in public opinion, rather than legislation, brought about a decline in dueling in the decades leading up to the Civil War. After the war, dueling was no longer popularly accepted in American society.

“The code of honor had lost much of its force, possibly because the country had seen enough bloodshed to last several lifetimes,” writes Drake. “Dueling was, after all, an expression of caste—the ruling gentry deigned to fight only its social near equals—and the caste whose conceits it had spoken to had been fatally injured by the disastrous war it had chosen. Violence thrived; murder was alive and well. But for those who survived to lead the New South, dying for chivalry’s sake no longer appealed.”

Famous Duels in American History

Hamilton-Burr

The most famous duel in American history was fought between former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, a Federalist, and Vice President Aaron Burr, a Democratic-Republican. The two New Yorkers had been political enemies for more than a decade, and Hamilton had played a key role in keeping Burr from winning the presidency in 1800. Four years later, Hamilton vigorously campaigned against Burr’s bid for New York governor, prompting Burr to challenge Hamilton to a duel.

On July 11, 1804, at the dueling grounds in Weehawken, New Jersey, Burr shot Hamilton in the stomach. Hamilton died the next day. Burr was charged with murder, though he was never tried. His image was forever tainted and his political career was destroyed.

Jackson-Dickinson

Nearly two decades before he became president, Andrew Jackson was nearly killed in a duel with Charles Dickinson, a horse breeder who had insulted him and his wife. Jackson, shot in the chest, killed Dickinson on his second shot after his first shot misfired.

“The ball that Charles Dickinson shot into Jackson, it was only about an inch or two from his heart,” The New York Times writes. “Clearly, it was a matter of inches that American history unfolded the way it did.”

Lincoln’s Near Duel

Abraham Lincoln nearly fought in a saber duel in 1842. After a disagreement regarding the state bank in Illinois, Lincoln humiliated his fellow state legislator, James Shields, in a letter to the editor of a newspaper. When Lincoln refused to retract the letter, Shields challenged him to a duel. The two arrived at the dueling grounds prepared to fight, but their seconds helped settle the dispute before the duel.