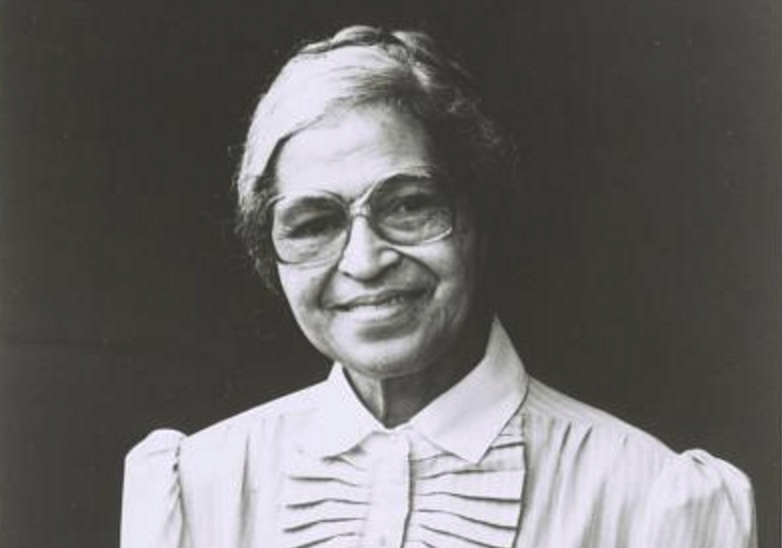

Rosa Parks was a seamstress and NAACP secretary whose simple act of civil disobedience—her refusal to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger—helped touch off the Civil Rights Movement.

Rosa Parks’ Early Days

Rosa Louise McCauley was born on Feb. 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Ala. In 1932, 19-year-old Rosa married Raymond Parks, a member of the NAACP who was involved in the Scottsboro boys case.

She joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP in 1943 and became a secretary. Her work with the organization included a leadership role in the NAACP Youth Council, and she helped organize a protest where black youths checked out books from white libraries.

Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

On Dec. 1, 1955, Parks was returning home from her job as a seamstress at a Montgomery department store. She boarded a city bus and took a seat in the first row behind the section reserved for white passengers under the city’s Jim Crow laws. When those 10 seats became filled, the bus driver ordered Parks and the three other black passengers seated in her row to stand up and make room for other whites.

The three other passengers moved, but Parks remained sitting. She was arrested and charged with “refusing to obey orders of bus driver.” Parks later recalled that, while she did not plan her protest, she had long been thinking about standing up to Montgomery’s racist laws.

“I felt that it was not right to be deprived of freedom when we were living in the Home of the Brave and Land of the Free,” she explained to the Academy of Achievement in 1995. “I had made up my mind that I would not give in any longer to legally imposed racial segregation.”

Some later accounts of Parks’ act portray her as a tired old woman who didn’t want to get up because her feet hurt. Parks disputed this notion. “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day,” she wrote in her autobiography “My Story.” “I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Within days, local civil rights leaders organized a boycott of Montgomery buses until the busing laws were overturned. Though Parks was not the first woman to refuse to give up her seat—two others had been arrested that year and others had been mistreated by bus drivers—she was chosen as the symbol of the protest because she was widely respected in the community and would appeal to a wider audience.

In his memoir about the bus boycott, Martin Luther King wrote, “Mrs. Parks was ideal for the role assigned to her by history. … Her character was impeccable and her dedication deep-rooted.”

The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted 381 days and ended after the Supreme Court ruled in Browder v. Gayle—a case involving the other women who had been arrested—that the city’s busing laws were unconstitutional.

After Montgomery

Parks lost her job as a seamstress in Montgomery and was unable to find work, just some of the short-term repercussions she (and many others) faced for her precipitous role in the civil rights movement. Parks left Alabama in 1957 and moved to Detroit, where she spent more than 20 years working for Congressman John Conyers. In 1987, she co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development to honor the legacy of her husband and the civil rights movement.

Among the numerous awards Park received were the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor, two of the highest awards granted in the United States.

Rosa Parks died in 2005 at the age of 92. Even in death she made history when she became the first woman and the second African-American to lie in state in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol.

Sources in this Story