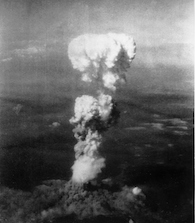

On Aug. 6, 1945, U.S. war plane Enola Gay dropped “Little Boy,” a 8,900-pound atomic bomb, on Hiroshima, Japan. Within eight days, Japan surrendered, ending World War II.

The Bombing of Hiroshima

The United States and Japan had been at war since 1941. By 1945, U.S. forces were closing in on the Japanese mainland and launching bombing attacks on Japanese cities.

On July 16, 1945, in the Trinity Test in New Mexico, the U.S. successfully detonated the world’s first atomic bomb. Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves, leader of the Manhattan Project, wrote to the secretary of war that the U.S. “now had the means to insure [the war’s] speedy conclusion and save thousands of American lives.”

Nine days later, on July 25, President Harry S. Truman and fellow Allied leaders, Josef Stalin and Clement Attlee, issued the Potsdam Declaration, an ultimatum for Japan to surrender unconditionally or face “prompt and utter destruction.” Japan refused to accept these terms on July 28.

Truman authorized the use of the atomic bomb as soon after Aug. 3 as possible. Four cities were selected as targets for their industrial and military importance: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki. Weather conditions would now determine when and where the first bomb would be dropped.

The 8,900-pound bomb, called “Little Boy,” was to be carried in a B-29 Superfortress piloted by Col. Paul W. Tibbets, commander of the 509th Operations Group. On Aug. 6, Tibbets and 11 crewmembers took off on the B-29—which the night before had been given the nickname “Enola Gay,” after Tibbets’ mother—from the island of Tinian toward Hiroshima, an industrial city and important military center.

At 8:15 a.m. local time, the Enola Gay dropped Little Boy onto Hiroshima. Just 43 seconds later it exploded 1,900 feet above the city. “Then the brilliant morning sunlight was slashed by a more brilliant white flash. … From the men who had rung up the curtain on a new era in history burst nothing more original than an awed ‘My God!,’” wrote Time.

Nearly five square miles, over 60 percent of the developed city, was destroyed. “All around, I found dead and wounded,” described one Japanese official. “Some were bloated and scorched—such an awesome sight, their legs and bodies stripped of clothes and burned with a huge blister. All green vegetation, from grasses to trees, perished in that period.”

It has been difficult to determine a definitive death toll. Between 70,000 and 80,000 of the more than 340,000 people in the city are believed to have been killed by the initial blast, and many more died in the following weeks and years from injuries and radiation. The official Japanese death toll, calculated a year after the explosion, is 118,661. Other estimates put the number of deaths at more than 140,000, while thousands of other victims have suffered from radiation sickness, cancer and other long-term effects.

For a detailed description of missions that dropped atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, read the report presented by the Manhattan Engineer District of the United States Army. It includes information on the cities and why they were chosen as targets, a summary of damages.

The Bombing of Nagasaki

The U.S. issued a press release threatening further destruction if Japan did not immediately surrender and dropped leaflets warning civilians to evacuate urban areas. Japan did not immediately accept surrender.

On Aug. 9, three days after the bombing of Hiroshima, the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki. This time, Japan accepted defeat and sought peace.

Japan accepted the Potsdam terms and unconditionally surrendered to the United States on Aug. 14, a day known as Victory in Japan, or V-J, Day. It marked the end of World War II.

Were the Bombings Justified?

Reactions to Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb are split. Many consider the bombing cruel and inhumane while others argue that the U.S. government was left with no alternative to end the war.

A feature in The Atlantic analyzes both sides of the story. It highlights Karl T. Compton’s “If the Atomic Bomb Had Not Been Used,” in which he notes “the nuclear explosions killed far fewer people than the firebombings.

Moreover, without the nuclear attacks, the Japanese would not have surrendered, even though they were militarily beaten: ‘I cannot believe,’ he wrote, ‘that, without the atomic bomb, the surrender would have come without a great deal more of costly struggle and bloodshed.’”

Thomas Powers offers a contrasting perspective in “Was It Right?” asking “how could the killing of 100,000 civilians in a day for political purposes ever be considered anything but a crime?” He does admit, however, that “the bombing was cruel … but it ended a greater, longer cruelty.”

George Washington University’s National Security Archive has an extensive selection of primary resources on the atomic bomb and the end of World War II. Documents range from letters between politicians debating first use alternatives to the earliest intercepted Japanese surrender memorandums.