On Aug. 7, 1964, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution based on what is now widely believed to be faulty intelligence, plunging the United States into the Vietnam War.

Congress Passes Resolution Following Tonkin Gulf Incident

President Lyndon B. Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara “grew concerned in early 1964 that the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), America’s ally, was losing its fight against Communist Viet Cong guerrillas,” writes the Naval Historical Center. “The American leaders decided to put military pressure on Ho Chi Minh’s North Vietnamese government in Hanoi, which directed and provided military support for the Communists in the South.”

They launched the covert Operation 34A, which called for the U.S. Navy to conduct raids off the coast of North Vietnam. Separately, the Navy also carried out surveillance operations; part of the operation was the USS Maddox, a navy destroyer that began reconnaissance missions northwest of the South China Sea, in the Gulf of Tonkin, on July 31, 1964.

On Aug. 2, in retaliation for an OPLAN-34A raid on July 31, three North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the Maddox. The torpedoes missed, and only a single machine gun round hit the American destroyer.

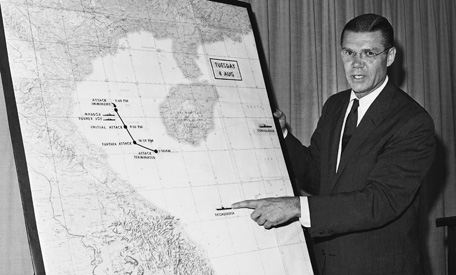

On Aug. 4, the Maddox and the USS Turner Joy returned to the gulf, anticipating another attack. That night, the Turner Joy picked up high-speed vessels on its radar, but the Maddox did not. The two destroyers fired on the supposed ships, though there was confusion whether there were actually attackers.

In response to the Aug. 4 incident, which became known as the “second attack,” President Johnson approved retaliatory air strikes and went on national television that night to announce the strikes. “Our response for the present will be limited and fitting,” he said. “We Americans know, although others appear to forget, the risks of spreading conflict. We still seek no wider war.”

Johnson also asked Congress to approve a resolution, known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, that authorized the president to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

The House passed Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in only 40 minutes, with no dissenting voters. The Senate needed nine hours, but there were only two opposing votes, from Democrats Wayne Morse of Oregon and Ernest Gruening of Alaska. They both contended that it was unconstitutional because it represented a “predated declaration of war power.”

“I believe that history will record that we have made a great mistake in subverting and circumventing the Constitution of the United States,” argued Morse. “I believe this resolution to be a historic mistake. I believe that within the next century, future generations will look with dismay and great disappointment upon a Congress which is now about to make such a historic mistake.”

What Happened and What Did Johnson Know?

The events of Aug. 4 have long been disputed and there is substantial evidence that there never was an attack on the Maddox. Johnson himself questioned the attack a few days later, saying that “those dumb, stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.”

Many historians and opponents of Johnson have charged the attack was a fraud used as propaganda to win support for the war. In a report for NPR, Walter Cronkite argued that McNamara planned for the attack. He cites a conversation that occurred just hours before the attack in which McNamara explained the situation to Johnson.

“He didn’t say ‘could be attacked’ or ‘might be attacked,’ he said ‘to be attacked tonight.’ Washington was clearly laying bait for the fox. American bait to justify American retaliation,” said Cronkite.

In 2001, National Security Agency historian Robert Hanyok published a report in the in-house journal Cryptologic Quarterly that showed the NSA skewed and withheld evidence. “The overwhelming body of reports, if used, would have told the story that no attack had happened,” he argued. “So a conscious effort ensued to demonstrate that an attack occurred.”

Hanyok does not believe that there were political reasons for the NSA’s actions. Rather, he believes that mid-level NSA agents distorted evidence to cover up earlier mistakes. Furthermore, he found no evidence that Johnson or any White House official knew or condoned the skewed evidence.

Pentagon historian Edward J. Drea, writing in MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, describes the confusion among White House officials in the days surrounding the attack. He contends that the Johnson administration felt forced to make a quick and decisive response that was influenced by unreliable information and a pattern of North Vietnamese aggression.

Hanyok’s report was released to the public in 2005 as part of the declassification of more that 140 top secret NSA documents, including histories, intelligence reports and interviews.

Biography: Lyndon Johnson

Johnson was elected in 1960 as vice president to John F. Kennedy and became president three years later after the assassination of President Kennedy.

Johnson was in the midst of a contentious presidential race against Republican nominee Barry Goldwater when the Gulf of Tonkin incidents occurred. He would go on to win the election with over 60 percent of the electoral vote.

Throughout his presidency, American involvement in Vietnam drastically increased. As the war dragged on with end in sight, Johnson lost the support of the American people. During the Democratic primaries for the 1968 election, a beleaguered Johnson pulled out of the race.