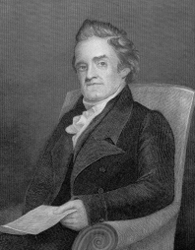

Noah Webster was a pioneering thinker devoted to books and learning. After the American Revolution, he set out to help the United States develop a distinctly American culture and an educational system all its own, and gave the country some of its most popular dictionaries.

Noah Webster’s Early Days

Noah Webster was born on a farm in West Hartford, Connecticut, on October 16, 1758. His father mortgaged his house to send young Noah to Yale. He took a break from university to serve in the American Revolution. After graduation, Webster studied law part time and supported himself with a teaching job.

Webster’s Notable Accomplishments

As a teacher, Webster became frustrated by the absence of American culture in available textbooks. This led him to start developing a “distinctively American education,” according to Biography.com. One of his first steps was to create the “American Spelling Book,” often referred to as the “Blue-Backed Speller.” To date, it has sold at least 100 million copies and was the main source of Webster’s income throughout his life.

Sources in this Story

- Amherst College: Noah Webster, 1758–1843

- Merriam-Webster Online: Noah Webster and America’s First Dictionary

- The New Yorker: Life and Letters about Noah Webster and the writing of his “American Dictionary of the English Language”

- The Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society: Noah Webster History

- Worcester Telegram & Gazette News: Talk keeps audience spellbound

- Yale University Office of Public Affairs: Noah Webster Fêted for 250th Birthday

Webster also felt that the new country’s language should have its own spelling and pronunciation. He published “A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language” in 1806, which Merriam-Webster Online calls “the first truly American dictionary.”

Webster’s crowning achievement was “An American Dictionary of the English Language.” He announced his plan to create the book on June 4, 1800, by taking out an advertisement in a Connecticut newspaper. His plans garnered national attention, and many believed his idea was ridiculous. Some people worried that Americans were trying to be too innovative. Members of society’s elite didn’t take to Webster’s philosophy that “common people” helped shape a country’s language, and others were opposed to his idea of changing the spelling of words like “women” and “tongue” to “wimmen” and “tung.”

Defying the opposition, Webster pursued his idea. After learning 26 languages and spending 25 years writing more than 70,000 entries, he published the work in 1828.

The Man and his Work

- “American Dictionary of the English Language (1828 Facsimile Edition)”

- “Noah Webster’s Advice to the Young and Moral Catechism”

- “Noah Webster: The Life and Times of an American Patriot” by Harlow Giles Unger

- “Noah Webster and the American Dictionary” by David Micklethwait

The Rest of the Story

While his dictionaries gave Webster some of his greatest notoriety, and earned him the title “schoolmaster to America,” he also produced multiple political letters and essays. He wrote a series of reflective essays in the 1830s, which were based on the “political mayhem” he perceived when Andrew Jackson became president. Chief among his philosophies was Webster’s belief that a person should gain social position by merit, not by birth.

When Noah Webster died in 1843, two brothers, Charles and George Merriam, purchased the unsold copies of Webster’s “American Dictionary of the English Language.” The Merriams, who owned a print shop and bookstore, realized “how ideally suited dictionary publishing was for general demand,” according to John Morse, president and publisher of Merriam-Webster Inc. The Merriams obtained the rights to revise Webster’s dictionary, and made sure it was affordable for people to buy (the $20 price of the dictionary was also enough to buy a grandfather clock).

Webster’s legacy will likely continue for a long time, says Mr. Morse. “Noah Webster predicted that American English would become the world’s most important language, a prediction that today has been borne out.”

October 16, 2008, marked Webster’s 250th birthday.

This article was originally written by Lindsey Chapman; it was updated October 17, 2017.