Born into a life of religion, Martin Luther King Jr. used his faith to help guide a divided nation toward racial equality, breaking barriers and demanding change through a strict code of nonviolence.

King’s Early Days

The third in a line of southern pastors, King was born Michael Luther King Jr. on January 15, 1929 in Atlanta, Ga., where his father and grandfather had both held pastoral positions at the city’s Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Following a family tradition, King earned a B.A. from Morehouse College in 1948, going on to study at Crozer Theological Seminary in 1951 and earn a doctorate from Boston University in 1955. In Boston he met Coretta Scott, the woman he would come to marry.

Accepting his first pastoral role at Montgomery, Ala.’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church the year before earning his Ph.D., King arrived at the pulpit just in time to be swept up in history.

The Early Years of the Civil Rights Movement

Although King was already an executive member of the NAACP, his leadership role in the fight for equality in the American South occurred seemingly by chance.

Picked to host a meeting to support an African American woman, Rosa Parks, who had been arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus, King’s church was chosen not for the young pastor’s words or deeds, but because it was located closest to downtown. However, King answered fate with a call to action that would launch a 13-year period of activism and leadership solidifying his name in history. King’s approach to freedom would be come to known for its use of “the power of words and acts of nonviolent resistance.”

Led by King, Alabama boycotted the bus system for over a year. The Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 was King’s first taste of what it would be like as a controversial public voice challenging the status quo. His life was threatened, his house was bombed and he was incarcerated on numerous occasions.

However, inspired by the nonviolent mantra of his spiritual and political inspiration, Mahatma Gandhi, whose teachings King first discovered while studying at the Crozer Theological Seminary, King persisted in the face of anger and opposition, eventually bringing about the Supreme Court ruling outlawing bus segregation. The boycott was one of the first victories for the civil rights movement and it established a model for nonviolent protest.

Another of King’s influences was Frederick Douglass, called the “forefather of the civil rights movement.” An activist and former slave, Douglass was a key figure in the journey from emancipation to desegregation.

Having become a family man, King shifted his efforts to a larger struggle for racial equality, helping to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957 to organize churches to further the cause.

King appeared on national television for the first time in February 1957 on the talk show “Open Mind.” He was introduced as a “new negro,” one who is willing to stand up and demand his rights, rather than act submissively like a “happy, acquiescent slave.”

Using his faith to anchor his words and deeds, King fast became the spiritual and political voice of African Americans, rallying supporters to his side in a flurry of appearances and demonstrations demanding change, though his efforts never strayed from his pledge to nonviolence.

The years that followed would be his most prolific, travelling 6 million miles, writing five books and garnering international acclaim that led to him becoming the youngest person to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Birmingham and “I Have a Dream”

In 1963 King led protests in the heavily segregated city of Birmingham, Ala., drawing thousands to the southern town to challenge racial division. By the time the protest had been halted, hundreds, including King himself, had been arrested, but not before Police Chief Eugene “Bull” Connor had used excessive and violent force against those gathered.

From jail, King penned his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” defending the protest to critics and capturing a message for change, concluding, “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

In 1963, 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Negro American Labor Counsel leader A. Philip Randolph, who in 1941 had planned a march in Washington to protest the exclusion of blacks from national defense jobs, organized a march along with leaders of the most prominent civil rights organizations: Jim Farmer (CORE), Martin Luther King (SCLC), John Lewis (SNCC), Roy Wilkens (NAACP), and Whitney Young (Urban League).

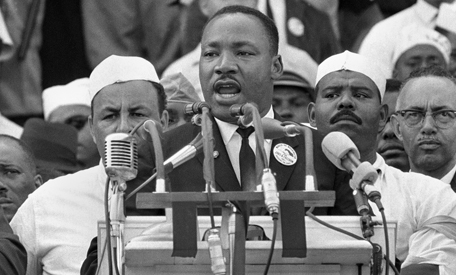

Between 200,000 and 300,000 people gathered at the National Mall for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which featured speeches by civil rights, religious and labor leaders, as well as singing performances and prayers. King’s speech was delivered near the end of the event.

At once a political call to action and deeply spiritual sermon, the Southern Baptist preacher began by painting a grim picture of a nation in need of change. Providing a historical case for change, King appealed to the crowd with a “fierce urgency of now.”

Having established the dire state of affairs for minorities in the United States, King made an appeal to “not wallow in the valley of despair.”

What followed would become one of the most often-cited public texts in American history, though it was not part of King’s original draft. Drawing on previous speeches he had made, King delivered a series of short stanzas that began with “I have a dream.”

He ended his speech proclaiming, “When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! free at last! thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

King was named Time’s Man of the Year for 1963.

Voting Rights Act and the Nobel Peace Prize

On July 2, 1964, the work of King and the civil rights movement was finally rewarded, when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in public places and forbid racial discrimination by private employers.

In March 1965, 3,200 civil rights demonstrators began a march from Selma, Ala., to Montgomery to protest the South’s discriminatory voting laws. “By the time they reached the capitol on Thursday, March 25, they were 25,000-strong,” according to the National Parks Service. The march was the catalyst for the Voting Rights Act, which was passed less than five months later. The act outlawed disenfranchisement through literacy tests and poll taxes, and allowed the federal government to intervene in areas with apparent discrimination.

Coupled with the harsh footage of Connor’s police force in Birmingham, King’s efforts were credited with bringing about the passage of both laws. In October 1964, at the age of 35, King became the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Focus on Vietnam

Celebrated as he was, King’s final years represented a departure from the civil rights movement. Instead he focused on larger economic and political issues, namely the war in Vietnam.

“Nothing will ever taste any good for me until I do everything I can to end that war,” he told advisors, pushing a plate of food away as he read through a report on napalmed youth in Vietnam, according to The Washington Post.

This shift in focus and the resentment of those within his own camp who believed his pledge to nonviolence was outdated often left King alone and exhausted in his final years. However, King appeared no less determined to bring about the change he felt the world should see, including guaranteed income for all Americans, an end to poverty and a conclusion to the war in Vietnam.

The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

It was with that energy and determination that King arrived in Memphis, Tenn., in April 1968, to offer a sermon on the future of the United States and to support a sanitation workers strike. On April 3, he delivered a speech now called “I’ve been to the mountaintop,” in which he stated, “I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

The following day, while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Hotel, King was shot. He collapsed and was taken to nearby St. Joseph’s Hospital, where emergency surgery failed to save his life. He died just over an hour after being shot.

Robert F. Kennedy, speaking at a campaign rally that night, echoed the ideals that King had lived and died for: “What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.”

Police arrested escaped convict James Earl Ray, who pled guilty and was sentenced to life in prison. Ray later recanted and said he had been set up. Nonetheless, his confession was upheld eight times and he died in prison in 1998. Some King family members agreed with Ray, charging that King was a victim of a government conspiracy designed to end the major anti-poverty reforms he had planned.

Reference: Documenting the Civil Rights Leader’s Life

Stanford’s King Institute is the Web’s best resource for researching the life and work of Dr. King. Find text and audio of his speeches, sermons and papers in the King Papers Project or learn about his life in the King Encyclopedia.

The Seattle Times provides a slide show of photographs of King’s life, a biography and links to additional stories related to his legacy, including his wife Coretta Scott King’s death.