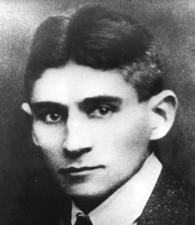

Living a life tortured by his own insecurity and lack of connection to the world around him, Franz Kafka found comfort in his writing, which examined the surreal, illogical and baroque aspects of modern life.

Franz Kafka’s Early Days

Franz Kafka was born in Prague on July 3, 1883. Franz was the oldest child of six children—though two of his brothers died as infants—and the only living boy. His family was middle class, and his father Hermann Kafka owned a store selling clothing and accessories. According to Mauro Nervi of The Kafka Project, the logo that Hermann used for the store was a jackdaw—a raven-like bird and the meaning of the family’s Czech name, “Kavka.”

Numerous sources mention that Kafka was most likely raised by a governess or nanny, and that his parents spent much of their time at the family store. Franz was not especially close to his mother, and he was constantly seeking approval from his father, but Hermann’s high standards left Franz with an ever-present feeling of failure. Encyclopedia Britannica points out that many of Kafka’s works include figures representative of his relationship with his father.

During Kafka’s childhood, Prague was part of Austria-Hungary, so German was Kafka’s first language. Often during that time, German speaking Jewish people were disliked by Czech nationalists and Germans alike. According to the Kafka Museum, Franz’s mother Julie Löwy was more devout to their Jewish religion than his father, who loosely upheld the Jewish practices.

Sources in this Story

- Franz Kafka Museum: Franz Kafka

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Franz Kafka

- The Kafka Project by Mauro Nervi: Biography

Kafka’s “Double Life”

Kafka was an excellent but unconfident student. He was admitted to Charles University in Prague, where he first studied chemistry, switched to German studies, and then settled on studying law. During college Kafka continued to write as he had done since he was a young boy, and he joined a literary club at school where he met his lifelong friend and fellow literary intellectual, Max Brod.

After receiving his doctorate, Kafka began working for an insurance company and he stayed in this field of work for the remainder of his life. He spent his nights writing, a habit that affected his personal life.

“Kafka was a charming, intelligent, and humorous individual, but he found his routine office job and the exhausting double life into which it forced him (for his nights were frequently consumed in writing) to be excruciating torture, and his deeper personal relationships were neurotically disturbed,” writes Encyclopedia Britannica.

Although some of Kafka’s most well-known works were published after his death, he did publish work during his lifetime. Some of his first work was published in the magazine “Hyperion” in 1908, and later he published short stories and prose in other publications as well as a few books. In 1912 he began to write what might be his most famous work, “The Metamorphosis,” and it was published in 1915. A complete timeline of when Kafka wrote and published his works can be found at the Franz Kafka Museum Web site.

During his years writing and publishing, Kafka spent summers and holidays vacationing with his close friends (including Max Brod) and often, according to Nowak and Ruch, used the holidays to regain his health (which he never felt was in great shape). Kafka also had a number of romances. He was engaged to three women during his lifetime (he was engaged to one woman, Felice Bauer, twice) but never married.

The Man and His Work

Kafka’s Posthumous Recognition

Kafka was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1917, after which he never fully regained his health. In 1922 he left his job and worked on his health and his writing, traveling to and from Prague in his final years. Franz Kafka died on June 3, 1924.

Although most of Kafka’s work is known for its pessimism, sense of despair and strange mix of reality and the supernatural, many sources note that Kafka in life was an easy man to get along with, a hard worker and even somewhat humorous.

His longtime friend Max Brod is responsible for publishing Kafka’s work. Although Kafka had requested that all of his letters, diaries and manuscripts be burned upon his death, Brod took all of the writing that he could find and had it published.

Kafka’s work grew from being known only in small circles to being internationally revered. Unfortunately, during the decades that followed his death, both of his parents passed away, and all three of his sisters were killed in concentration camps.

This article was originally written by Haley A. Lovett; it was updated May 31, 2017.