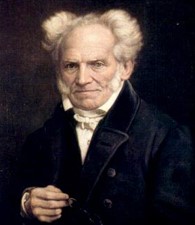

A notoriously pessimistic philosopher who aspired to give meaning to the human condition through the appreciation and analysis of art, Arthur Schopenhauer challenged the depictions of the perceptual world put forth by Plato and Emmanuel Kant. A lonely and difficult man who lived a life that matched his own grim philosophy, he ultimately believed that art and sympathy could save man from suffering.

Early Days

Arthur Schopenhauer was born to parents of Dutch descent on February 22, 1788, in Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland). Danzig was annexed by Prussia when he was five; his family left the country for Hamburg, Germany, and also spent years traveling through Europe. As a young man, he enrolled in a business apprenticeship in Hamburg and began to thrive intellectually, despite a lack of passion for a commercial life. It was his father who determined he ought to enter the world of commerce, and he pursued the path for two years after his father’s death out of respect, his biography on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy says.

Schopenhauer attended the University of Göttingen, but eventually moved on the University of Berlin; he began his academic career in the natural sciences, but soon shifted to the humanities. He read Plato and Immanuel Kant, philosophers whose theories of reason he would come to challenge. Schopenhauer completed his dissertation, “The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason,” at the University of Jena, earning a doctor of philosophy degree.

Sources in this Story

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Arthur Schopenhauer

- Biography.com: Arthur Schopenhauer Biography (1788–1860)

- BBC Radio 4: In Our Time’s Greatest Philosopher Vote: Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860)

- Oregon State University: Great Philosophers: Arthur Schopenhauer

- Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Harper’s magazine: No Comment: Six Questions for Arthur Schopenhauer

Notable Accomplishments

Schopenhauer’s nickname was the “philosopher of pessimism.” He believed that the will was the cause of unhappiness, and challenged many of the philosophers of his time by asserting that the will was more powerful than reason. He elucidated this point in his most famous work, “The World as Will and Representation.” The BBC reports that much of his philosophy is actually a reflection of his personality and life experiences. He lived a mostly solitary existence without friends or love. Although he had been close with his mother, a famous writer, and she had introduced to him to members of her literary circle, including Goethe, they would eventually differ over lifestyle choices and became estranged. Ultimately, aesthetic experience would be Schopenhauer’s antidote to the misery of the human condition inflicted by the will.

He secured a teaching position at the University of Berlin, but no one attended his lectures, as he insisted upon scheduling his lectures at the same time as the increasingly renowned and popular Hegel. Schopenhauer left Berlin for Italy. He later unsuccessfully reapplied for his teaching position, and spent the rest of his days alone, studying and writing.

Schopenhauer’s divergence from the concept of reason and his contemporaries who advocated it, such as Hegel, might have accounted for some of his unpopularity. He was the first Western philosopher to seriously incorporate Eastern ideologies into his works. Schopenhauer’s ideas about how man could be freed from the burden of will and desire coincide with the Buddhist description of the Eightfold Path. Schopenhauer also believed that there is no external world, it merely appears in virtue of man’s will that it should be there.

The Man and His Work

- “The World as Will and Representation”

- “On The Basis of Morality”

- “Essays and Aphorisms”

- “Schopenhauer” by Robert Wicks

The Rest of the Story

Later in life, Schopenhauer’s work began to receive more positive attention, winning prizes and good reviews. He died in Frankfurt on September 21, 1860.

Schopenhauer’s philosophy influenced many other great thinkers, including Sigmund Freud and Friedrich Nietzsche. Modern philosophers continue to debate where he fits in the analytic tradition. A recent book on Schopenhauer by Robert Wicks was well-reviewed in the Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, but a great deal of reviewer Robert Guay’s criticism centered on Schopenhauer’s interpretations, not Wick’s. For example, “The World as Will” begins with Schopenhauer’s own description of Kant’s philosophy, and his challenges to it. But many philosophers feel that Schopenhauer’s understanding of both Kant and Plato was incorrect.

Still, among intellectuals and other curious folk, an interest in the controversial man and philosopher remains. Harper’s magazine blog No Comment did a semi-humorous, semi-educational fake interview with the long dead philosopher in 2007. In “Six Questions for Arthur Schopenhauer,” author Scott Horton makes fun of the poodles Schopenhauer kept as pets during the last half of his life, summarizes some of the key underpinnings of his theories, and collects recommended summer reading for the Harper’s audience.

This article was originally written by Rachel Balik; it was updated January 6, 2017.