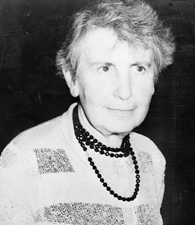

Tirelessly devoted to both her renowned father and his revolutionary but controversial psychoanalytic theory, Anna Freud was Sigmund Freud’s youngest daughter, and sole heir to his clinical tradition. She was an innovator in her own right, largely credited with developing theories regarding the emotional lives of children, as well as a committed teacher and advocate.

Anna Freud’s Early Days

Anna Freud, the youngest of Sigmund Freud’s six children, was born December 3, 1895. The Freud Museum reports that she had an unusually mischievous temperament but that it didn’t bother her father; rather he was charmed by her “naughtiness.” However, Freud constantly competed with her elder sister Sophie, a rivalry that only subsided when Sophie married. Anna Freud herself would never marry; instead, she focused on her career and carrying on her father’s tradition.

After leaving school in her birthplace of Vienna, Freud traveled to England, seeking to become a more adept speaker of the language. She was sent back when World War I broke out; she then began her career as a teacher at the school where she had studied, the Cottage Lyceum. Uncertain of her career aims, Freud pursued her interests in psychoanalysis alongside her job teaching elementary school. She was never forthcoming about the motivation for her psychoanalytic pursuits, but her Reuters obituary notes that many speculated she was drawn to analysis out of admiration for her father.

As a young woman, she read her father’s works, and Sigmund Freud began psychoanalyzing her when she was 23 years old. She soon began contributing her own theories and research, attending conferences and working as a psychoanalyst herself.

Her career as a teacher led her to ultimately focus on child psychology, but she was diligently and wholly committed to perpetuating her father’s work, even as she developed her own.

Sources in this Story

- Freud Museum: Life and Work of Anna Freud

- The New York Times (Reuters): Anna Freud, Psychoanalyst, Dies in London at 86

- Shippensburg University: Anna Freud 1895–1982 by Dr. C. George Boeree

- Britannica Online Encyclopedia: Anna Freud

- The Adoption History Project: Anna Freud (1895–1982)

- Anna Freud Centre

Anna Freud’s Notable Accomplishments

The younger Freud took her father’s theories and used them to study children. Her father had worked solely with adults and thus many of his ideas about childhood development were purely theoretical; his daughter emphasized more hands-on and research-based applications with actual children. She is widely considered to be an innovator in child psychology as a practice. She was also responsible for seminal work in the area of ego psychology and establishing the nature of repression.

She developed her concept of repression by examining the various ways children seek to protect themselves physically and emotionally from dangers. Her work on various defense mechanisms contributed to adolescent psychology as well.

Freud and her father left Austria during World War II and moved to London. There, she helped to establish the Hampstead Child Therapy Clinic, where she conducted most of her research. She encountered numerous children made parentless by the war, and developed essential literature on adoption, establishing that in most cases, adoption was far healthier for children than placing them in institutions. The Adoption History Project site notes that her work not only applied to adopted children, but also to the nature of parent-child relationships and infant psychology in general.

The Woman and her Work

- “Anna Freud: A Biography, Second Edition” by Elisabeth Young-Bruehl

- “The Technique of Child Psychoanalysis: Discussions with Anna Freud” by Joseph Sandler, Hansi Kennedy and Robert L. Tyson

- “Psychoanalysis for Teachers and Parents” by Anna Freud

- “Normality and Pathology in Childhood: Assessments of Development 1965” by Anna Freud

- “Before the Best Interests of the Child” by Joseph Goldstein, Anna Freud and Albert J. Solnit

The Rest of the Story

Freud never married, although she was constant companion to her father and served as his caretaker after he was stricken by cancer in 1923. She lived out her life dedicated both to her own work, and to the future of psychoanalysis, which deeply concerned her. Despite attacks on the credibility of psychoanalysis and questions about whether Freud’s devotion was to her father and not the tradition, she believed that the theory could enrich lives.

Freud was also a strong advocate for children’s rights and ensuring that they remained protected. After her death on October 10, 1982, the Hampstead Clinic continued as the Anna Freud Centre, a nonprofit dedicated to helping children.

This article was originally written by Rachel Balik; it was updated December 4, 2017.