1. Lincoln Nearly Died After Being Kicked by a Horse

In an 1859 autobiographical letter, Lincoln mentioned a near-death experience at age 10. Writing in the third-person, Lincoln said, “In his tenth year he was kicked by a horse, and apparantly (sic) killed for a time.”

William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner, described the incident in greater detail in his 1889 biography “Herndon’s Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life.” Young Abraham was whipping the horse and yelling, “Get up, you old hussy” when “the old jade, resenting the continued use of the goad, elevated her shoeless hoof and striking the young engineer in the forehead, sent him sprawling to the earth.”

Lincoln was knocked unconscious and remained in that state until the next morning when the “blood beginning to flow normally, his tongue struggled to loosen itself, his frame jerked for an instant, and he awoke, blurting out the words ‘you old hussy,’ or the latter half of the sentence interrupted by the mare’s heel at the mill.”

Edward J. Kempf, a neurologist and psychiatrist, theorized in his 1965 book that the incident caused cerebral damage and contributed to the “melancholy” he felt throughout his life.

2. Lincoln Briefly Served in a Militia During the Black Hawk War

Lincoln’s only military experience came in 1832, when, at age 23, he volunteered for the Illinois Militia, which was preparing to fight the Sac and Fox Indian tribe led by Black Hawk. Lincoln was elected captain of a company, but he did not see any combat action during his two months of service.

Lincoln would often speak humorously about his military experience. In an 1848 speech before the House of Representatives, he declared, “Did you know I am a military hero? Yes, sir; in the days of the Black Hawk war I fought, bled, and came away. … I had a good many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes, and although I never fainted from the loss of blood, I can truly say I was often very hungry.”

3. Lincoln Almost Fought a Saber Duel

After a disagreement regarding the state bank in Illinois, Lincoln humiliated a fellow state legislator, James Shields, in a letter to the editor of a newspaper. When Lincoln refused to retract the letter, Shields challenged him to a duel.

Lincoln set the conditions of the duel to his advantage, choosing sabers instead of pistols and stipulating that the combatants stand on a long, thin plank while dueling, allowing the much taller Lincoln to exploit his superior reach. The two men gathered at Bloody Island, an island between Illinois and Missouri that was frequently used for dueling, on Sept. 22, 1842. Shortly before the duel was to take place, mutual friends of Lincoln and Shields convinced the two to call it off.

Lincoln preferred to not speak of the duel. “If all the good things I have ever done are remembered as long and as well as my scrape with Shields, it is plain I shall not be forgotten,” he once said.

4. Lincoln Was the Only President to be Granted a Patent

Lincoln had a life-long interest in mechanics and inventions. “Man is not the only animal who labors; but he is the only one who improveshis workmanship,” he noted in an 1858 lecture on inventions.

Lincoln, who steered flatboats down the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers in his youth, developed an idea for a device that would help lift boats over sandbars using inflatable bellows attached to the hull. Lincoln and mechanic Walter Davis developed a scale model that Lincoln used to secure Patent 6469 in 1849.

According to William Herndon, Lincoln foresaw the patent leading to a “revolution” in steamboat navigation. However, the device was impractical and, said Herndon, “was never applied to any vessel, so far as I ever learned, and the threatened revolution in steamboat architecture and navigation never came to pass.”

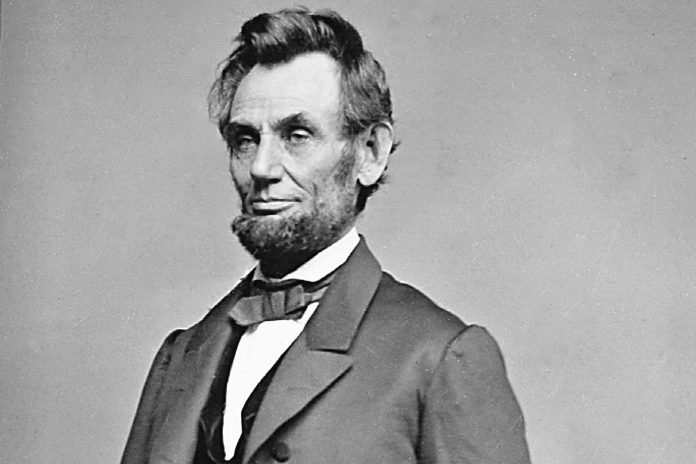

5. Lincoln Was the First President to Grow a Beard

Lincoln was clean-shaven when he began running for president. He grew a beard after receiving a letter from Grace Bedell, an 11-year-old girl from New York, in October 1860, a few weeks before the election. Grace said that with a beard he “would look a great deal better for your face is so thin.” Furthermore, she wrote, “All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you and then you would be President.”

Lincoln responded to Bedell a few days later in a letter. “As to the whiskers, having never worn any, do you not think people would call it a piece of silly affectation if I were to begin it now?” he wrote.

By growing a beard, Lincoln nearly bankrupted a young entrepreneur named Milton Bradley, who had a booming business selling daguerreotypes of the clean-shaven candidate. Bradley destroyed his supply of daguerreotypes and turned to board games to make money.

6. Lincoln Likely Suffered From Depression

Lincoln was often described as suffering from melancholy during his life and his own letters suggest that he was prone to bouts of depression. William Herndon said of him, “He was a sad-looking man; his melancholy dripped from him as he walked. His apparent gloom impressed his friends, and created sympathy for him—one means of his great success. He was gloomy, abstracted, and joyous—rather humorous—by turns; but I do not think he knew what real joy was for many years. … The perpetual look of sadness was his most prominent feature.”

Lincoln likely would have been diagnosed with clinical depression if he were alive today. Joshua Wolf Shenk wrote in his 2005 book “Lincoln’s Melancholy” that Lincoln “could be used in a psychiatry textbook to illustrate a typical depression.”

However, Shenk also argued that Lincoln’s depression drove him to become a great president. During the dark days of the Civil War, Shenk says, “The suffering he had endured lent him clarity and conviction, creative skills in the face of adversity, and a faithful humility that helped him guide the nation through its greatest peril.”

7. Lincoln Did Not Intend to Free the Slaves When He Became President

Although Lincoln became a national figure speaking against the institution of slavery, he had no plans to end slavery as president, believing that the Constitution “forbade me to practically indulge my primary abstract judgment on the moral question of slavery.”

Lincoln’s primary objective as president was to preserve the Union: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it,” he wrote to New York Times editor Horace Greeley.

Lincoln later decided to emancipate Southern slaves as a way to redefine the Civil War and instill greater significance to the Northern cause. In September 1862, he announced his intention to release slaves in rebelling areas effective Jan. 1, 1863, when he officially released the Emancipation Proclamation. Henceforth, the Civil War would be fought not just to preserve the Union, but also to abolish slavery.

8. Lincoln Was Not the Keynote Speaker at Gettysburg

Lincoln was invited to the opening of the Gettysburg cemetery on Nov. 19, 1963, and asked to make “a few appropriate remarks,” after the keynote speaker, Edward Everett. Everett spoke for two hours before Lincoln delivered one of the most famous speeches in American history in the span of just a few minutes.

The following day, Everett sent a note to Lincoln expressing admiration for the “eloquent simplicity” of his brief remarks. Lincoln responded, “In our respective parts yesterday, you could not have been excused to make a short address, nor I a long one. I am pleased to know that, in your judgment, the little I did say was not entirely a failure.”

9. John Wilkes Booth’s Brother Saved the Life of Lincoln’s Son

In a remarkable twist of fate, Edwin Booth, the older brother of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth, saved the life of Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s son, in 1863 or 1864. While waiting for a train, Robert Lincoln fell in the gap between a train and the station platform.

Robert Lincoln described in 1909 that he was “personally helpless, when my coat collar was vigorously seized and I was quickly pulled up and out to a secure footing on the platform.” Edwin Booth, who unlike his brother was a Union sympathizer, pulled him up by his coat.

10. Lincoln Survived an Assassination Attempt, But His Bodyguard Still Left Him Alone at Ford’s Theatre

Lincoln received many threats to his life during his presidency and was nearly killed in August 1864. Alexander McClure, a friend of Lincoln, presented an account of the apparent assassination attempt in his 1900 biography “Lincoln’s Yarns and Stories.”

A soldier guarding Lincoln’s home heard a shot and went to examine the president, finding him without his hat. “On going back to the place where the shot had been heard, we found the President’s hat,” the soldier described. “It was a plain silk hat, and upon examination we discovered a bullet hole through the crown.”

Lincoln did not think it was an assassination attempt and did not see the need for increased security regardless. “I long ago made up my mind that if anybody wants to kill me, he will do it,” said Lincoln.

That November, Lincoln received a four-man security team. On the night of his assassination at Ford’s Theatre, just one man, a policeman with a dubious record named John Parker, was protecting the president’s box. Parker left the area to get a better view of the play and later to drink outside the theater, leaving the president unprotected when Booth killed him.

11. Lincoln’s Body Has Been Moved 17 Times, And Was Nearly Stolen

On the day of his assassination, Lincoln formed the Secret Service, the organization now tasked with protecting the president. The Secret Service was created to combat counterfeiting, rather than to protect the president, but it did manage to protect Lincoln well after his death.

In 1876, a Chicago-based counterfeiting ring schemed to steal Lincoln’s body from its unguarded tomb in the Oak Ridge cemetery in Springfield, Illinois, and hold it for ransom. The plot was to be carried out by two men, Terence Mullen and Jack Hughes, but neither had any experience stealing bodies, so they recruited a third man, Lewis Swegles. Swegles, however, was an informant for the Secret Service.

Mullen and Hughes attempted the heist on Nov. 7, 1876—election night—but they found that they were unable to lift the 500-pound coffin that was lined with lead. Furthermore, Swegles alerted authorities who moved in on the two men and were soon able to arrest them.

For a host of reasons, Lincoln’s body was exhumed and moved 17 times after his burial. Finally, it 1901, a new tomb was constructed. After his coffin was partially opened and 23 witnesses confirmed that Lincoln’s body was inside, it was encased in 4,000 pounds of cement.