On February 24, 1868, Andrew Johnson became the first U.S. president to be impeached; the Senate subsequently acquitted him by a single vote.

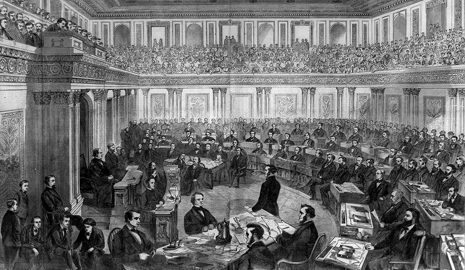

House Impeaches President Johnson

Andrew Johnson was sworn in as president after President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865. Lincoln, a Republican, had chosen Johnson, a Democrat who served as military governor of Tennessee, as his running mate for re-election in 1864 because he was a southerner who supported the war and was loyal to the Union.

The main issue facing Johnson was how to readmit the Southern states that had seceded. He opposed military rule over Confederate states, pardoned rebel soldiers and returned property to rebels. He also vetoed two bills passed by the Republican-controlled Congress that established rights for freed slaves.

Johnson’s Reconstruction policies angered many Republicans and gave rise to the Republicans’ radical wing. As the conflict between Johnson and Congress intensified, the radicals looked for a reason to have Johnson removed from office.

Their opportunity came when Johnson dismissed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a holdover from Lincoln’s cabinet, without the permission of Congress, which voted 35 to six against the move. Johnson, knowing that he would be violating the Tenure of Office Act if he replaced Stanton, decided on February 21, 1868, to name a new secretary of war.

Just three days later, February 24, the House voted 126 to 47 to impeach Johnson for violation of the Tenure of Office Act and other “high crimes and misdemeanors,” the first time in U.S. history that the president was impeached.

The Senate impeachment trial of Johnson began March 30, 1868, with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding. Because Johnson did not have a vice president, his successor would have been the president pro tempore of the Senate, Ben Wade of Ohio, described by historian Eric Foner as “a man disliked by moderates for his radical stance on Reconstruction, and by many businessmen and laissez-faire ideologues for his high tariff, soft-money, prolabor views.”

The prospect of a Wade presidency caused moderate Republicans to think twice about Johnson’s removal. On May 16, after a six-week trial, the Senate held its vote on impeachment. Needing 36 votes to impeach, the prosecution had 35 votes committed when Republican Senator Edmund Ross of Kansas, an undecided voter, was called.

Historian David Dewitt writes, “The whole audience listens for the coming answer as it would have listened for the crack of doom. And the answer comes, full, distinct, definite, unhesitating and unmistakable. The words ‘Not Guilty’ sweep over the assembly, and, as one man, the hearers fling themselves back into their seats; the strain snaps; the contest ends; impeachment is blown into the air.”

Sources in this Story

- The Constitutional Rights Foundation: Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- The New York Times: Debate in the House on the Impeachment Resolution

- U.S. National Parks Service: The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- University of Missouri-Kansas City: The Impeachment Trial of Andrew Johnson Impeachment

- George Mason University: History Matters: The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- University of Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs: Andrew Johnson

- Time: An Impeachment Long Ago: Andrew Johnson’s Saga

Biography: Andrew Johnson (1808–75)

Andrew Johnson was raised in a North Carolina log cabin with nearly illiterate parents. The family later moved to Tennessee, where Johnson met his future wife, who taught him to read. He became involved in politics and was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1856.

Though he was allied with the pro-slavery, pro-state’s rights Democrats, he did not believe that the South should secede from the Union. When Tennessee seceded, Johnson chose to remain in the Senate, the only Southern senator to do so. He was branded a traitor in the South, but he was a hero in the North and his decision made him an attractive vice presidential choice for Lincoln in 1864.

Johnson opposed freedom for slaves and convinced Lincoln to make Tennessee exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation. He remained sympathetic to Southerners and was a poor replacement for Lincoln in establishing the policies of post-war Reconstruction.

“For the most part, historians view Andrew Johnson as the worst possible person to have served as President at the end of the American Civil War,” writes the Miller Center of Public Affairs. “Because of his gross incompetence in federal office and his incredible miscalculation of the extent of public support for his policies, Johnson is judged as the greatest failure of all Presidents in making a satisfying and just peace.”

Reference: Trial Primary Sources

Harper’s Weekly features a collection of primary source articles and cartoons about Andrew Johnson and his impeachment. It also includes biographies of important figures involved in Johnson’s impeachment.

The University of Missouri-Kansas City provides the Senate trial record, as well as the opinions of several congressmen and a map illustrating the final vote. It also explains the legal issues of impeachment, the impeachment process and the Tenure of Office Act.

Historical Context: The Civil War (1861–1865)

The findingDulcinea Web Guide to the Civil War links to the most comprehensive and reliable sources on the war.

Related Topic: Impeachment of Bill Clinton

In December 1998, President Bill Clinton became the second U.S. president to be impeached. He was charged with perjury and obstruction of justice for lying in a deposition about a sexual affair with intern Monica Lewinsky. He was acquitted by the Senate by a sound margin.

Time’s Adam Cohen found several similarities between the two impeached presidents. “Like some of Clinton’s televised explaining and finger wagging, Johnson’s p.r. offensive hurt his cause,” he wrote, adding, “Political and character assassination was alive and well long before cable TV and the Internet.”