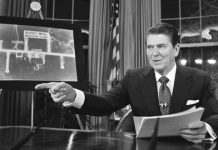

On February 5, 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented Congress with legislation intended to manufacture Supreme Court approval for his New Deal.

“Court-Packing” Bill Fails in Congress

During the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to alleviate countrywide hardship with governmental aid and public works projects. With Democrats controlling Congress by a large majority, Roosevelt had the full support of the legislature to pass his New Deal legislation.

But the president faced opposition from the Supreme Court, which included four conservative justices—known as the “Four Horsemen”—and two justices who usually voted with the horsemen. Together, the six justices ruled that many of Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives were unconstitutional.

In response, Roosevelt put forward the Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937. Claiming that aging justices were falling behind in their caseloads, Roosevelt proposed that he be allowed to appoint an additional justice to the court for every justice who was over 70 years old.

The court was not behind in its work, and Roosevelt’s true intention was clear: to mold a court more favorable to his New Deal. The “court-packing” bill, as the plan came to be known, immediately came under fire from both Republican opponents and Democratic allies.

Roosevelt defended the bill in a fireside address on March 9, 1937. “The balance of power between the three great branches of the federal government has been tipped out of balance by the courts in direct contradiction of the high purposes of the framers of the Constitution,” he said. “It is my purpose to restore that balance.”

Sources in this Story

- Smithsonian Magazine: Showdown on the Court

- New Deal Network: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Judicial Branch Reorganization Plan

- Oyez Oyez Oyez: Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary, March 9, 1937

- The Boston Globe: Did FDR’s threat to ‘pack’ the court in 1937 really change the course of constitutional history?

- University of Virginia: American Studies: Court Packing: Judicial Reorganization and the End of the New Deal

- The New York Times: Stacking the Court

On March 29, the court upheld the constitutionality of minimum wage legislation in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, as Justice Owen Roberts, who commonly voted with the Four Horsemen, voted with the liberal block. Some argue that Justice Roberts was influenced by the threat of Roosevelt’s bill, and his decision became known as “the switch in time that saved nine.” However, many modern historians believe that Roberts made his decision before Roosevelt unveiled his plan.

Later that spring, the Supreme Court would uphold the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) and Social Security plan as constitutional. In May, Justice Willis Van Devanter, one of the Four Horseman, retired, allowing Roosevelt to appoint a replacement. Roosevelt’s measure was defeated in committee. Over the next five years, seven of the nine justices retire or died, allowing Roosevelt to shape the Supreme Court as he pleased.

“Roosevelt had a Court he could live with…but the damage had been done,” explains Paul Volpe of the University of Virginia. Roosevelt lost a good deal of support in the legislature and was unable to expand on his New Deal policies. “Although a few laws would be passed in 1938,” concludes Volpe, “the politics and economics of the last years of the decade brought the New Deal to a close.”

Background: The Great Depression and the New Deal

PBS provides a timeline of the Great Depression and the New Deal, from the stock market crash of October 1929 to Roosevelt’s election to a third term in 1940.

Biography: Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Roosevelt was born into a life of wealth and politics in Dutchess County, New York. He attended Harvard and Columbia Law School, and became involved in New York politics. After his stint as assistant secretary of the Navy, Roosevelt was elected governor of New York, but not before being stricken by polio. However, the disease did not halt his career and he was elected president in 1932.

Historical Context: Manipulating the Supreme Court

The number of Supreme Court justices has changed several times since it began in 1789 with six justices. It was nearly reduced to five in 1800 by opponents to incoming President Thomas Jefferson, but later increased to seven by Jefferson supporters to give him an additional nomination.

The number increased to nine during the administration of Andrew Jackson, and to 10 during the Civil War to allow for an additional anti-slavery justice. Congressional Republicans refused to allow President Andrew Johnson to make appointments, reducing the number to seven. When Johnson was succeeded by Ulysses S. Grant, the court was expanded to nine justices, allowing Grant to nominate two justices in favor of the government’s desire to issue paper money.

“There is nothing sacrosanct about having nine justices on the Supreme Court,” writes Jean Edward Smith, author of “FDR.” “Roosevelt’s 1937 chicanery has given court-packing a bad name, but it is a hallowed American political tradition participated in by Republicans and Democrats alike.”