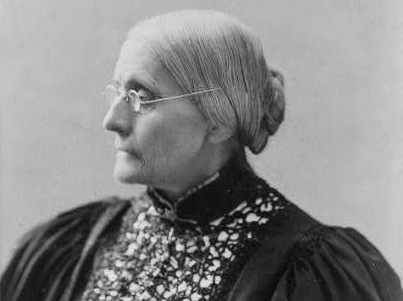

On Nov. 5, 1872, 48 years before the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote, women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony and a group of women in Rochester, N.Y., cast votes in the presidential election.

Anthony Arrested for Casting Vote

Susan B. Anthony had been dedicating her life to the women’s rights movement since the early 1850s. After the Civil War, when Congress sought to pass an amendment granting black males the right to vote, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton led the call for the right to be extended to women.

“Meeting little success, they adopted a ‘new departure’ strategy, which interpreted the 14th Amendment as granting all naturalized and native born Americans citizenship, believing that particular status inherently conferred suffrage rights,” explains the Office of the Clerk.

On Nov. 1, 1872, she led a group of women, including her three sisters, to a voter registration office in Rochester, N.Y., and demanded that they be allowed to register under the protections of the 14th Amendment. Women in other parts of the country did the same, but they would not have the success of Anthony.

Anthony, according to Ann D. Gordon of Rutgers University, did not anticipate that she would be allowed to vote. Rather, “she expected to be denied registration as a voter and subsequently to sue for her right to vote in federal court.”

Election inspectors initially refused to register Anthony, but she argued for over an hour. Finally, after threatening to take the matter to court, she convinced the election inspectors to register her and other 14 women.

“She asked me if was acquainted with the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of the U.S. I told her I was,” recounted Mr. Beverly Jones, an inspector. “She wanted to know if under that, she was a citizen and had the right to vote. At this time, Mr. Warner, the election supervisor, said, Young man, how are you going to get around that? I think you will have to register their names.”

Four days later, Anthony arrived at the West End News Depot in Rochester to cast her votes. Anthony voted for every Republican on the ballot, including President Ulysses S. Grant. Two of the three inspectors voted to allow the votes, making them official.

In a letter to Stanton, she wrote, “Well I have been & gone & done it!! … If only now—all the women suffrage women would work to this end of enforcing the existing constitution—supremacy of national law over state law—what strides we might make this winter.”

Anthony’s Arrest and Trial

On Nov. 14, U.S. Commissioner William Storrs issued a warrant for the arrest of Anthony and the 14 other women for voting “without having a lawful right to vote,” a violation of Section 19 the Enforcement Act of 1870. The three election inspectors would also be arrested.

Four days later, a deputy marshal visited Anthony’s home and asked that she turn herself in to Storrs’ office. However, she demanded that she be “arrested properly,” forcing the deputy to handcuff her and take her to Storrs. In January 1873, a grand jury indicted Anthony.

Out on bail, Anthony toured through towns around Rochester, giving speeches on women’s rights. “It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union,” she proclaimed. “And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government—the ballot.”

At trial in June, Anthony’s attorney argued that she did not violate the Enforcement Act, which specifies that a person cannot “knowingly” vote illegally, because she believed that she had the right to vote. He also used the trial to espouse the beliefs of the women’s suffrage movement.

Backed by recent Supreme Court cases that restricted the definitions of citizenship under the 14th Amendment, Judge Ward Hunt ruled that the amendment did not guarantee women the right to vote. He also found that Anthony was aware that she could not legally vote, and decided to issue her a fine for $100 plus the costs of the prosecution. Anthony refused, and authorities made little effort to ever collect the fine.

In a separate trial, the election inspectors were also issued fines, which they refused to pay. They were arrested and detained for a month until President Grant issued pardons.

A year after Anthony’s trial, the Supreme Court ruled in Minor v. Happersett that states were not required to allow women the right to vote. Having lost two major court decisions, the women’s suffrage movement soon abandoned its strategy to attain the vote through the court system and began focusing on a campaign for a constitutional amendment.

Historical Context: Women’s Suffrage Movement

The suffrage movement grew out of the abolitionist and temperance movements of the mid-19th century, as women involved in those efforts became politically active. In 1848, about 250 suffragists including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott gathered for the historic Seneca Falls women’s rights conference in New York.

In the post-Civil War period, when men gained the right to vote with the 15th Amendment, several prominent suffrage organizations were created, including Stanton and Anthony’s National Woman Suffrage Association and Lucy Stone’s American Woman Suffrage Association, which were later combined to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

An amendment to the constitution guaranteeing women the right to vote was introduced to Congress in 1878, but it wouldn’t be passed for another 41 years. In 1890, Wyoming became the first state to give women the right to vote, and nine other states had followed by 1912.

By 1916, the Democratic and Republican parties both endorsed the enfranchisement of women. The tide took a decisive turn in favor of women when New York adopted women’s suffrage in 1917 and President Woodrow Wilson announced his support of the amendment in 1918.

The 19th Amendment, which stated, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex,” was ratified on Aug. 18, 1920.