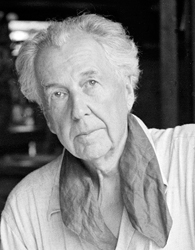

The most famous architect in American history, Frank Lloyd Wright sought to unify man and nature through his compelling architectural designs. The man behind “Prairie School,” Fallingwater and the Guggenheim Museum, he brought upon himself as much controversy as success.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Early Days

Frank Lincoln Wright was born in Wisconsin, on June 8, 1867, to Anna Lloyd Jones and William C. Wright. (He changed Lincoln to Lloyd as an adult.) Much of Wright’s childhood was spent on the move: the family lived in Iowa, Rhode Island and Massachusetts, before heading back to Wisconsin.

From 1885 to 1886, Wright studied engineering at the University of Wisconsin, but his aspirations were already in architecture. He headed to Chicago the following year, where he served as an apprentice to architect J. L. Silsbee. This position led to work as a draftsman for Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan. His new firm was selected to design the Auditorium Building, which became the tallest building in Chicago upon its completion.

Sources in this Story

- The Biography Channel (Encyclopedia Britannica): Frank Lloyd Wright

- Wright on the Web: A Virtual Look at the Works of Frank Lloyd Wright

- PBS: Frank Lloyd Wright: Life and Work

- The New Yorker: Spiralling Upward

- The BBC: Mystery of the murders at Taliesin

Wright’s Architectural Career

Buoyed by the bustling architectural scene and his innate self-assurance, Wright formed his own company in 1893. When he turned down a lucrative offer by fellow Chicago architect Daniel Burnham to run his firm in Europe, it was clear that Wright had his eyes set on transforming the American architectural landscape.

Wright became the most prominent practitioner of the “Prairie School” style of architecture, which was more open and expansive than the boxed European style. The nexus of Midwestern commercial building and rural construction, it provided Wright with certain aesthetic tenets that would guide him throughout his career.

Residential designs were flat and sleek, playing upon the lines and curves of the surrounding land. Interiors were expansive and blurred the boundaries between individual rooms. Building methods tapped into the tricks of urban planning; purchased materials were often mass-produced, thereby cutting costs. It’s ironic that his major achievement from this period was nonresidential: the Unity Church in Oak Park, Illinois.

Wright introduced the concept of “organic” architecture, the idea that a structure should be integrated naturally with its surroundings. In a 1957 interview with Mike Wallace, Wright explained it was “architecture that belonged where you see it standing—and is a grace to the landscape instead of a disgrace.”

In the aftermath of the stock market crash of 1929, Wright shifted gears and focused on writing and lecturing. He also established the Taliesin Fellowship, which brought a number of aspiring architects and artists to his estate every year.

As the economy began to convalesce, Wright received two commissions: one for a house in the Allegheny Mountains and another for the S.C. Johnson administrative offices. The former project, known as Fallingwater, would become his most famous creative achievement. Positioned over a waterfall, the residence has a number of Wright trademarks: cantilevered strips, overlaid geometric motifs and a design scheme that responds to the natural environment.

The S.C. Johnson building was revered for the grandeur of its interior. Columns with mushroom-like tops rise from the floor and soften sheets of ceiling light, rendering the massive space more intimate.

Nearly 70 years old, Wright was in high demand. And he was still capable of churning out bold and innovative designs with his renowned aplomb. One of his last works was the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which was completed six months after his death at the age of 91.

Though the design received more than its fair share of criticism, even from James Johnson Sweeney, the director of the museum, many have come to view it as a fitting cap to Wright’s career.

This view is particularly intriguing, because Wright spent much of his life synthesizing his architecture with nature. The Guggenheim, conversely, was entwined in the manmade grid: perpendicular streets, cubic buildings, a sea of rectangular windows. If the challenge was to break up the city’s linear scheme, he undoubtedly succeeded.

“The bulbous form emerged from behind flat-fronted apartment buildings like a balloon in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade,” wrote Paul Goldberger in The New Yorker.

On the inside, the spiral ramp and haloing skylight imbue the interior with an otherworldly beauty. Because the ramp winds around a central atrium, one can see where one was and where one will be.

Wright’s Personal Life

Wright married to Catherine Tobin in 1889 while working for Adler and Sullivan. By the early 1900s, however, the couple had become so estranged that Wright began seeing Mamah Cheney, the wife of a former client, and took off with her for Europe, leaving Tobin and his children behind.

Upon their return, he built the Taliesin estate in Spring Green, Wisconsin. In September 1914, while Wright was in Chicago, a disgruntled worker, Julian Carlton, set fire to Taliesin, killing Cheney, their children, and several friends. Those, including Cheney, who broke and jumped from windows trying to flee were met by Carlton and his hatchet.

Wright wrote a letter to his neighbors, both a tribute to Mamah Cheney and a defense of their relationship: “I cannot bear to leave unsaid things that might brighten memory of her in the mind of anyone. But they must be left unsaid. I am thankful to all who showed her kindness or courtesy and that means many. No community anywhere could have received the trying circumstances of her life among you in a more high-minded way.”

This article was originally written by Devin Felter; it was updated May 18, 2017.