On March 11, 1977, Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, leader of the Nation of Islam splinter group Hanafi Movement, ended a three-day siege of three buildings in Washington, D.C. Twelve Hanafi gunmen had taken 149 people hostage, two of whom were killed.

American Hanafi Movement Takes Over D.C. Buildings

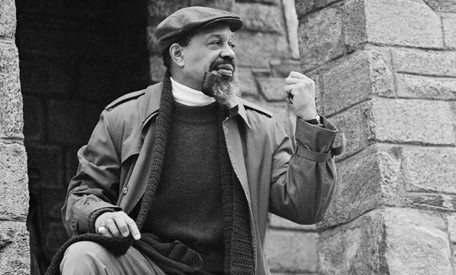

Former Nation of Islam (NOI) National Secretary Khalifa Hamaas Abdul Khaalis (born Ernest Timothy McGee) had broken from the organization and founded the Hanafi Movement in 1968. In 1973, rival Black Muslims killed six of Khaalis’ family members; though five of the killers were sentenced to life in prison, the case pushed the mentally unstable Khaalis over the edge.

On March 9, 1977, he and 11 other armed Hanafi members attacked the Washington, D.C., headquarters of Jewish cultural organization B’nai B’rith International. Within hours, the gunmen had also seized the District of Columbia’s city hall and the adjacent Islam Center, and taken a total of 149 people hostage.

One man, 24-year-old reporter Maurice Williams, was shot dead during the siege, while a wounded security guard would die days later of a heart attack. Others were injured, including D.C. Council member Marion Barry, the future mayor, who was shot in the chest.

Khaalis made many demands and threatened to start beheading people if his demands were not met. He ordered that his family’s killers be turned over to him while condemning the Jewish judge who presided over the case, repeatedly shouting that “Jews control the courts and the press.” He also wanted to speak with NOI founder Wallace Muhammad and boxer Muhammad Ali, a prominent NOI member.

Two of Khaalis’ other demands were met. He was reimbursed the $750 in contempt of court citations he incurred during the trial of the Black Muslims and he received a promise that showings of the film “Mohammad, Messenger of God” would be halted. Khaalis considered the film to be blasphemous and his “concern over the film was thought to have triggered the attack,” wrote Time.

As the siege dragged on into a third day, three ambassadors from Muslim-majority countries aided law enforcement. Egypt’s Ashraf Ghorbal, Pakistan’s Sahabzada Yaqub-Khan and Iran’s Ardeshir Zahedi negotiated with Khaalis by citing phrases from the Koran that stressed compassion. Khaalis soon relented under the condition that he be allowed to return home.

After the siege ended, Khaalis and three of his accomplices were released without bail, which was one of the conditions to end the siege.

Those involved in the siege were arrested, tried, and received sentences of at least 24 years. Khaalis was sentenced to 41 to 123 years.

Sources in this Story

- Time: The 38 Hours: Trial by Terror

- The Washington Post: “Some Things You Never Forget”

- Center for Integration and Improvement of Journalism at San Francisco State University: News Watch: Islam in the United States

- JTA: Joy, Tears, Prayers and Sorrow Mark End of 39-hour Siege

- Google News Archive/The Free Lance-Star: No apologies, says Khaalis after Hanafis are sentenced

- Southern Poverty Law Center Teaching Tolerance: American Muslims in the United States

- NPR: A History of Black Muslims in America

- YouTube: Hanafi Siege in Washington (Part 1)

- Global Security: Hanafi Islam

The Siege and the Dangers of Terrorism

The siege occurred at a time when Americans were just beginning to learn of the threat of terrorism. “The terrorists made dramatically clear what has become all too obvious: anybody with a cause and a gun, be he mad or madcap, fanatic or eccentric, can seize and hold national attention by kidnaping and threatening to kill innocent victims,” wrote Time in March 1977. “The Washington assault was the culminating event of a spate of terrorist acts that have bedeviled the country. It proved again how vulnerable the society is to such attacks.”

Daniel S. Mariaschin, executive vice president of B’nai B’rith International, told The Washington Post in 2007, “This was an early wake-up call about violence and terrorism and the extent to which groups will go to engage in violence either for the sake of violence or to make a point.”

YouTube has a segment from a news show called “Who’s Who” in which Dan Rather looked at how Khaalis dealt with the media during the siege.

Related Content

Background: History of Black Muslims and Hanafi Islam

The first documented arrival of Muslims in the United States was in the 17th century, and those who arrived were enslaved, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance project.

The first wave of free Muslim immigration didn’t occur until the late 19th century. After the Great Migration, in which African-Americans moved from the south to the north after World War II, African-Americans began to explore their Muslim African heritage.

Prominent Black Muslims such as Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X formed the image of American Muslims as black nationalists. For most Americans, this perception continued until the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, according to Howard University African studies professor Sulayman Nyang.

The Hanafi Movement was a small faction of the Black Muslims. It fashioned itself as a part of the traditional Hanafi school of Islam. Hanafi is considered the “oldest and most liberal” of the four schools of law within the Sunni Muslim faith, according to Global Security, which writes, “Broad-minded without being lax, this school appeals to reason (personal judgment) and a quest for the better. It is generally tolerant and the largest movement within Islam.”