On March 22, 1972, the Senate approved the Equal Rights Amendment, which banned discrimination on the basis of sex. The amendment fell three states shy of ratification.

Equal Rights Amendment Passed After 49 Years

In 1923, three years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote, suffragist Alice Paul drafted an amendment to guarantee equal rights for women. Known as the Equal Rights Amendment or the Lucretia Mott Amendment, it stated, “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

The amendment was presented to Congress in 1923, and re-introduced to every session of Congress for nearly 50 years. It mostly stayed in committee until 1946, when a reworded proposal, dubbed the Alice Paul Amendment, lost a close vote in the Senate. Four years later, the Senate passed a weaker version of the amendment that was not supported by ERA proponents.

Opposition to ERA came from social conservatives and from labor leaders, who feared that it would threaten protective labor laws for women. Support for the amendment increased during the 1960s as the Civil Rights Movement inspired a second women’s rights movement. The National Organization for Women (NOW), founded in 1966, led to movement for the passage of ERA.

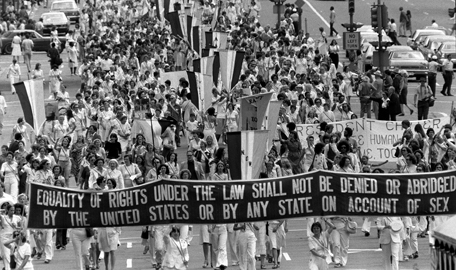

In 1970, Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan succeeded in getting the ERA out of committee and before Congress for debate. The House of Representatives passed the amendment without changes 352-15 in 1971. The Senate passed the amendment on March 22, 1972, a day after voting against any proposed changes.

The passed amendment read: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

The Senate set a deadline of seven years for state ratification. “Confidence that ratification would be achieved swiftly was expressed by a number of supporters of the amendment,” reported The New York Times.

The National Archives has copies of the proposals of the ERA to Congress made in 1923 and 1972. The Archives has a large collection of ERA documents.

Sources in this Story

- The Equal Rights Amendment: The History Behind the Equal Rights Amendment

- Library of Congress: The Long Road to Equality: What Women Won From the ERA Ratification Effort

- National Archives: Martha Griffiths and the Equal Rights Amendment

- The New York Times: Equal Rights Amendment is Approved by Congress

- The New Yorker: Firebrand: Phyllis Schlafly and the conservative revolution

- Eagle Forum: The Phyllis Schlafly Report: A Short History of E.R.A.

- National Organization for Women: Chronology of the Equal Rights Amendment, 1923-1996

ERA Falls Short of Ratification

The Equal Rights Amendment needed the ratification of 38 states to reach the required three-quarters majority. Thirty states ratified it within a year of the Senate’s approval, but only five more would follow in the next four years as grassroots opposition to the amendment mounted, most notably from Phyllis Schlafly’s Stop ERA and Eagle Forum organizations.

“Anti-ERA organizers claimed that the ERA would deny woman’s right to be supported by her husband, privacy rights would be overturned, women would be sent into combat, and abortion rights and homosexual marriages would be upheld,” writes Roberta W. Francis of the ERA Task Force.

According to the Phyllis Schlafly Report, “ERA advocates were unable to show any way that ERA would benefit women or end any discrimination against them. The fact is that women already enjoy every constitutional right that men enjoy and have enjoyed equal employment opportunity since 1964.”

Opposition may also have been fueled by a conservative backlash against the Roe v. Wade decision of January 1973 and the increasingly radical feminist movement, writes Leslie W. Gladstone for the Library of Congress.

In 1978, Congress extended the March 22, 1979, deadline for ratification to 1982; the extra three years made no difference, however, as no new states ratified the amendment. The ERA was left with the approval of just 35 states, five of which voted to rescind ratification between 1973 and 1979. The amendment was re-introduced to Congress in 1983, but fell six votes short of passage in the House.

Since 1983, the ERA has been re-introduced to each new session of Congress, but it has stayed in committee and there is little momentum for it to be passed. ERA-type legislation was most recently introduced in Congress in the 2017-2018 session.

Legacy of the ERA

Though the federal Equal Rights Amendment was never ratified, more than 20 states have added the protections of the ERA into their state constitutions. In addition, many significant sex discrimination laws were passed during the 1970s and ‘80s.

“The long public debate over the status of women and the call for a constitutional amendment heightened expectations that changes would be made, and changes did follow,” writes Gladstone.

Still, many women’s rights leaders remain disappointed with the failure of ERA. “If we passed the ERA we’d be in better shape, no question about it,” said former NOW President Eleanor Smeal in 2005. “We would have eliminated sex discrimination in insurance. We would have been better off in social security. Women are still getting 60 percent of what men are getting in social security. We’d have a better opportunity for equality in the military and we would have stronger laws for fighting sex discrimination, wages and education.”

Reference: Pro- and Anti-ERA Organizations

Several women’s rights organizations continue to actively advocate for the passage of the ERA. The Alice Paul Institute and the National Council of Women’s Organizations’ ERA Task Force operate the most notable ERA advocacy web site.

Conversely, Schlafly’s Eagle Forum continues to argue against ERA.

In 2012, we published this article about this historic event on The New York Times Learning Network. This article connected the event to current issues and offered reflection questions to help the reader think about its relevance today.