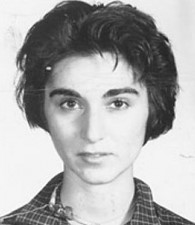

On March 13, 1964, Kitty Genovese was murdered in Queens, New York. An article that said 38 people ignored her screams during the attack generated a national scandal and prompted psychological studies on the behavior of bystanders.

“Thirty-Eight Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police”

Walking home at 3:15 a.m. on March 13, 1964, 28-year-old bar manager Catherine “Kitty” Genovese was attacked by Winston Moseley on a residential street in Kew Gardens, Queens. Moseley stabbed Genovese several times before being scared away by a man, Robert Mozer, who screamed “Hey, let that girl alone!” from his apartment.

Moseley returned to the scene about 10 minutes later and attacked a dying Genovese in an alleyway, stabbing her more and raping her as she died. The two attacks took place over 30 minutes, during which time at least 38 people saw the attack or heard Genovese scream, according to the police report.

Two weeks later, Martin Gansberg reported the story in The New York Times. “For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens,” he wrote.

He then proceeded to describe how Genovese’s pleas for help went ignored by her neighbors. Just one woman called the police, doing so after being alerted by a neighbor who said he “didn’t want to get involved.” A second witness made a similar remark, saying, “I didn’t want my husband to get involved.”

Gansberg documented other excuses given by witnesses. One couple thought the attack was nothing more than “a lover’s quarrel.” Another man, who Gansberg claimed was a witness to the second attack, explained “without emotion” why he didn’t call police: “I was tired. I went back to bed.”

National Outrage and “Genovese Syndrome”

The Times’ report sparked a national controversy over the inaction by the 38 bystanders, who were portrayed as self-centered and uncaring.

Psychological studies of the incident led researchers to coin the term “bystander effect,” or “Genovese syndrome,” which describes the phenomenon where an individual is less likely to act in an emergency situation if others are present.

In a study conducted by John Darley and Bibb Latane, individuals conversed over an intercom and one of them would pretend to have a seizure. When two people were involved, 85 percent of the participants went to help. With three people, 62 percent did something. With six people involved, only 31 percent went to help.

The study partly attributed these results to “diffusion of responsibility: When study participants thought there were other witnesses to the emergency, they felt less personal responsibility to intervene,” write Dacher Keltner and Jason Marsh in Greater Good magazine. “Similarly, the witnesses of the Kitty Genovese murder may have seen other apartment lights go on, or seen each other in the windows, and assumed someone else would help. The end result is altruistic inertia.”

Debunking the Kitty Genovese Myth

For years, the original Times article was the main source on the Genovese incident and few questioned its accuracy. However, recent examinations of the incident have found that the article was exaggerated and misleading.

Joseph De May, a lawyer and Kew Gardens resident, has closely investigated the incident. He describes that the initial attack, carried out in the front of a building, lasted just a few minutes. Genovese’s screams woke up many of her neighbors, but she managed to walk away when Moseley fled, giving the appearance that she was all right.

Genovese staggered to the back of an apartment building, out of sight for most people. According to De May, Genovese, who died of asphyxiation, likely would not have been able to call for help because her lungs had been punctured.

When Moseley returned to the scene about 10 minutes later, only one person could see or hear the second attack. This was the witness who “didn’t want to get involved” because, according to De May, he was drunk. He did contact a neighbor who called the police, but it was too late to save Genovese.

The number of neighbors who were in a position to judge the seriousness of the situation was far lower than 38. De May was told by the assistant prosecutor of the case that there were only “only maybe five or six people who saw anything that they could use.”

In American Heritage, Jim Rasenberger says the “perceptions of eyewitnesses and earwitnesses alike were mostly fleeting and inchoate.” Therefore, the reason that most of the witnesses didn’t respond was that they weren’t sure what was happening.

“It’s generally not stone-cold indifference that prevents people from pitching in during emergencies, psychologists now agree,” writes Rasenberger. “It’s states of mind more familiar to most of us: confusion, fear, misapprehension, uncertainty.”

Genovese’s younger brother Bill Genovese helped make a 2015 documentary, “The Witness,” that looks at how the myth surrounding his sister’s death was created, and the impact of it.

Sources in this Story

- Southeastern Louisiana University (The New York Times): Thirty-Eight Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police

- New York Magazine: How the False Story of Kitty Genovese’s Murder Went Viral

- Burlington County College: The Dying Girl that No One Helped

- University of California, Berkeley: Greater Good: We Are All Bystanders

- NPR (WNYC): On the Media: The Witnesses That Didn’t

- American Heritage: Nightmare On Austin Street

- New York Times: Kitty, 40 Years Later

- Sound Portraits: Remembering Kitty Genovese

- CrimeFeed.com: The Man Who Murdered Kitty Genovese: An Intimate Look at a Dangerous Mind

- New York Daily News: Keep on rottin’, Parole Board tells Kitty Genovese’s vile killer

- Vogue: The Witness Searches for Truth in the Kitty Genovese Story

Biography: Kitty Genovese

Catherine Genovese had grown up in Brooklyn, the oldest of five children. Her family moved to the Connecticut suburbs when she was 19 after her mother witnessed a shooting near the family’s home, but she stayed in New York. At the time of her death, she was managing a bar a few miles from her home.

Genovese was in a relationship with Mary Ann Zielonko for the last two years of her life. Zielonko told Sound Portraits Productions that at the time, “being a gay woman in that society was very hard.” They had concealed their relationship from many people, including Genovese’s family.

Zielonko said, “Kitty was the most wonderful person I’ve ever met. I still remember her face. I can see it in my mind: very Italian looking, very chiseled features, dark hair, like only about five feet tall. And very likeable person, very vibrant.”B

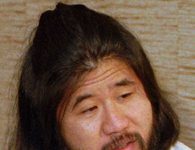

Biography: Winston Moseley

Moseley confessed to killing Genovese, but later gave several other stories of how Genovese died and why.

He was initially sentenced to death for Genovese’s murder, but his sentence was reduced to life in prison. He escaped in 1968 and went on a rampage that included taking five people hostage and raping a woman. He eventually surrendered.

He went before the parole hearing a few times, most recently in 2008, at the age of 72. The Parole Board denied Moseley’s request, and called him “violent and a danger.” He died in prison in 2016.

In 2012, we published this article about this historic event on the New York Times Learning Network. This article connected the event to current issues and offered reflection questions to help the reader think about its relevance today.